Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

A retrospective analysis of the number of episodes of single tooth extractions carried out under general anaesthetic on adult patients at University Hospital Wales Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) department over a 12-month period

A. Lockstone*1 BDS

V. Fairman2 BDS

S. Ali3 BDS, CertMedEd, DipConSed, M(Oral Surg), RCPS (Glasgow)

1Dental Core Trainee in Restorative & Paediatric Dentistry at Cardiff University Dental Hospital, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XW.

2Dental Core Trainee in Restorative dentistry, Oral surgery & Oral medicine at Cardiff University Dental Hospital, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XW.

3Consultant in Oral Surgery and Clinical teacher at Cardiff University Dental Hospital, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XW.

*Correspondence to: Dr Alice Lockstone

Email: alice_lockstone@hotmail.co.uk

Lockstone A, Fairman V, Ali S. A retrospective analysis of the number of episodes of single tooth extractions carried out under general anaesthetic on adult patients at University Hospital Wales Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) department over a 12-month period. SAAD Dig. 2025: 41(I): 17-21

Abstract

Introduction

Conscious sedation is perceived to be a safer technique than general anaesthetic (GA) to manage dental anxiety, and potentially allows for a higher turnover of patients at lower cost. Currently there are no official selection criteria for adult dental extractions under GA.

Objectives

This study investigates adult single tooth extractions (STE) under GA within the OMFS department at University Hospital of Wales (UHW), focusing on the number of episodes, their justification, and whether alternative techniques could have been used.

Method

Data was collected retrospectively, encompassing all scheduled episodes of adult STEs under GA across two UHW sites over one year.

Results

A total of 216 dental GA episodes were performed, 20% of which were STEs. Among these, 29% were for simple exodontia. The main reason for STE under GA was patient anxiety (42%), many specifically stating patient demand. No anxiety measures were recorded in the cohort's notes. Additionally, 73% of patients had tolerated dental treatment without GA, while 12% had prior GA experience. The mean waiting time was 84 weeks, with operations averaging 47 minutes, including anaesthesia.

Conclusion

A significant proportion of dental GA prescriptions appeared driven by patient anxiety rather than clinical need.

Key learning points

- A significant proportion of single tooth extractions under general anaesthetic are driven by patient anxiety rather than clinical necessity, highlighting the need for clear selection criteria

- Prescription of general anaesthetic for dental procedures should be carefully considered due to its risks of morbidity and mortality as well as its impact on NHS resources and waiting times for those who genuinely require it

- Conscious sedation is a safer and more cost-effective alternative to general anaesthetic, and its appropriate utilisation could reduce waiting times and optimise resource allocation

Introduction

The significant number of paediatric extractions under general anaesthetic (GA) is well documented in the literature and was the most common reason for paediatric hospital admissions in 2019/20.1 The issues surrounding over prescription of GA in adults is less well reported but equally a concern due to the array of available alternative anaesthetic modalities. Unlike paediatric dental GA, for adults there are no specific guidelines or selection criteria.2 Therefore, the justification for adult GA is inherently subjective due to different clinicians’ perceptions, attitudes, experiences of patient anxiety and anticipated procedural complexity.3 Consequently, adult dental GA is often prescribed on a discretionary basis.

Guidelines for the recommended provision of GA for dental purposes are broad, simplistic and non-specific. The General Dental Council (GDC) stipulates that dentists must ‘manage patient anxiety appropriately’ and ‘act within the patient’s best interest’ but the same guidance also dictates that clinicians should only prescribe GA where there is an ‘overriding clinical need’. The Department of Health recommends that GA ‘should only be considered, in discussion with patients or their carers after all other options have been excluded'.5 While involving patients in shared decision-making is now considered compulsory to obtain informed and valid consent, it may promote patients to choose GA in circumstances which may not be clinically justified, or where other methods have not been exhausted.

Consideration should be given to the patient’s medical history, the nature and complexity of the procedure, anticipated access to the surgical site, behavioural indicators affecting patient or operator safety, as well as the patient’s ability to tolerate the procedure. The decision to prescribe a GA for dental treatment should always be considered carefully due to the small, but significant, risks of morbidity and mortality.6

A large volume of patients requesting GA for simple procedures ultimately results in an increased wait for those who genuinely require it. Long waiting times bring further burden to the NHS through the frequent necessity of interim interventions. A study ‘process-mining’ electronic health record data for child dental GAs over a four-year period showed many emergency appointments were required for temporary dressings, extirpations and antibiotics in the period while waiting for extractions under GA.7 These additional dental visits bring significant cost to the NHS and negatively impact the patient due to ongoing pain, sleepless nights and time off work.

Other UK research has shown that single tooth extractions (STEs) under GA were patient demand driven with none of their cohort having GA due to failure of sedation.8 From a public health perspective, there are many factors to consider when evaluating the impact of dental GAs on the NHS, with staffing, theatre utilisation, waiting times, patient satisfaction, administration, and expense all playing a role.

Conscious sedation is a safer technique compared to GA that allows a higher turnover of patients at a considerably lower cost. Appropriate utilisation of this service could free up lists and minimize waiting times for GA.9 Ultimately, there is a need to review the current provision of both GA and conscious sedation services within OMFS departments.

Methods

The inclusion criteria for this study were all scheduled episodes of STE under GA over a 12-month period (01 September 2021 to 01 September 2022) across two sites associated with Cardiff Dental School’s OMFS department (University Dental Hospital theatre (UDH) and the Short Stay Surgical Unit at the main hospital (SSSU)). Cases were identified retrospectively via the electronic booking / management system (Theatreman) and data collected from the patients’ case notes. All data was processed and stored in compliance with the Data Protection Act 2018.

Data collection fields included:

- Patient demographics (age, gender)

- Procedure undertaken and its relative complexity*

- Referral to Treatment Time (RTT) calculated from date of referral to date of GA

- Length of operation (including anaesthesia)

- Reason for GA

- Whether sedation was offered

- Previous experience of dental treatment without GA

- Previous experience of dental GA.

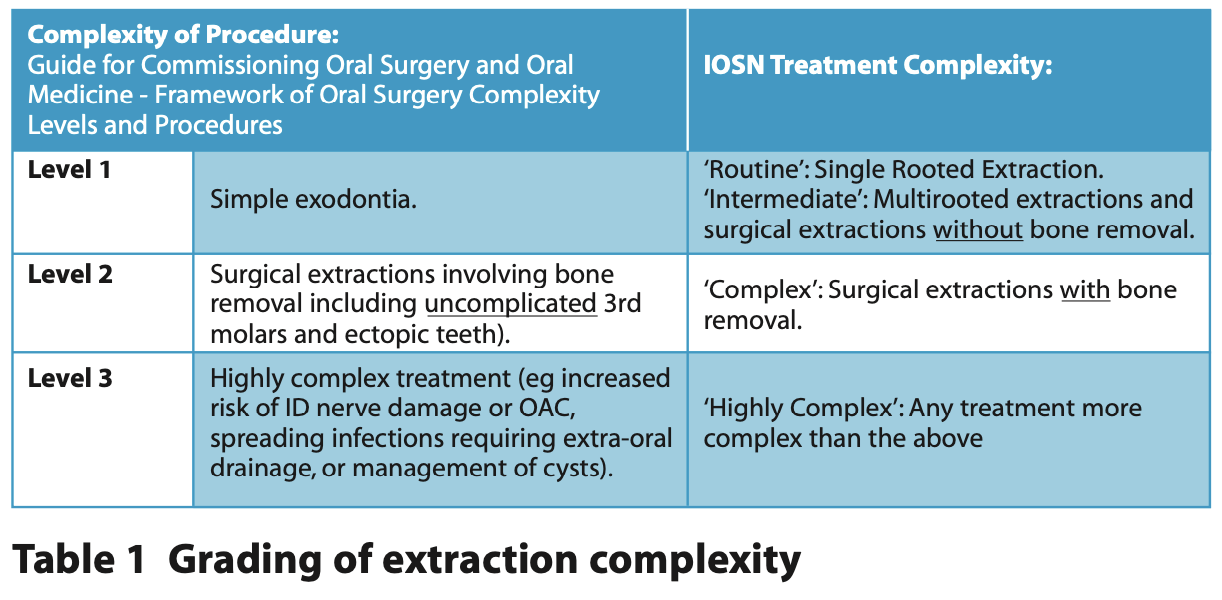

*The extraction complexity was graded as level 1, 2 or 3 according to the Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine - Framework of Oral Surgery Complexity Levels and Procedures.10 The way in which this grading system aligns with the Indictor of Sedation Need (IOSN) Treatment Complexity Score is summarised in Table 1.11

In summary, a Level 1 or ‘simple’ extraction involves single or multi-rooted extractions using elevation, forceps, and / or soft tissue manipulation (e.g. raising a flap), but without bone removal. A Level 2 or ‘complex’ extraction includes surgical extractions that require bone removal. Level 3 or ‘highly complex’ procedures involve extractions with a high risk of damaging anatomical structures including management of cysts or other pathology.

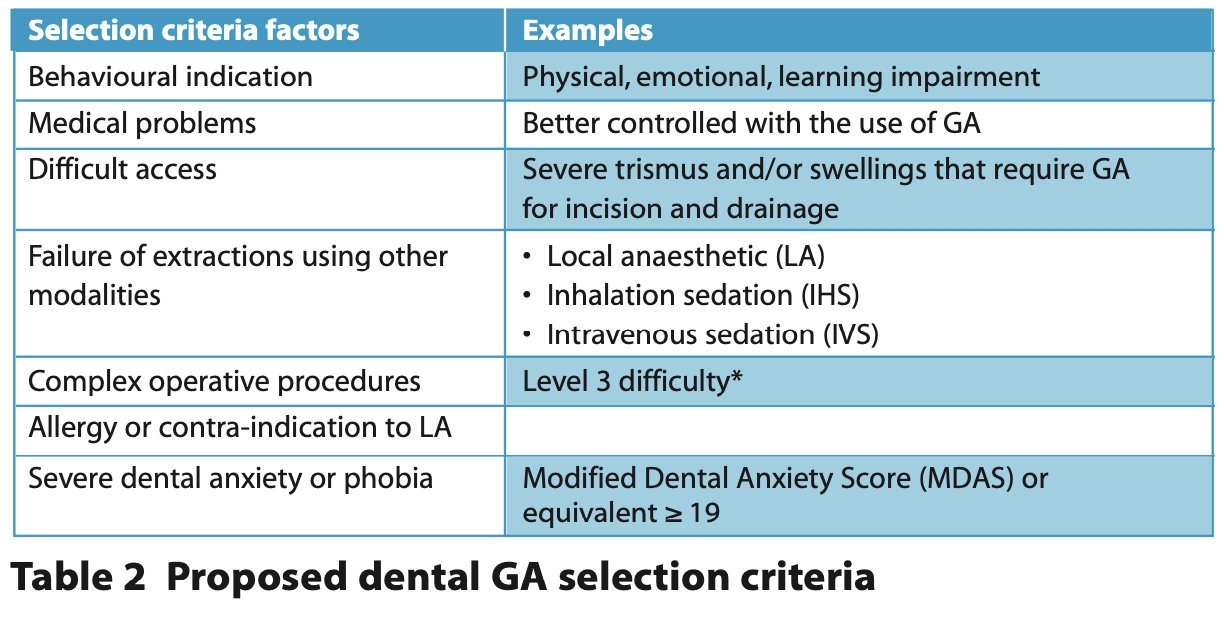

Each case was tested against GA selection criteria specifically devised for this service evaluation (Table 2) and is based on the suggested criteria used in other research.8

Results

General

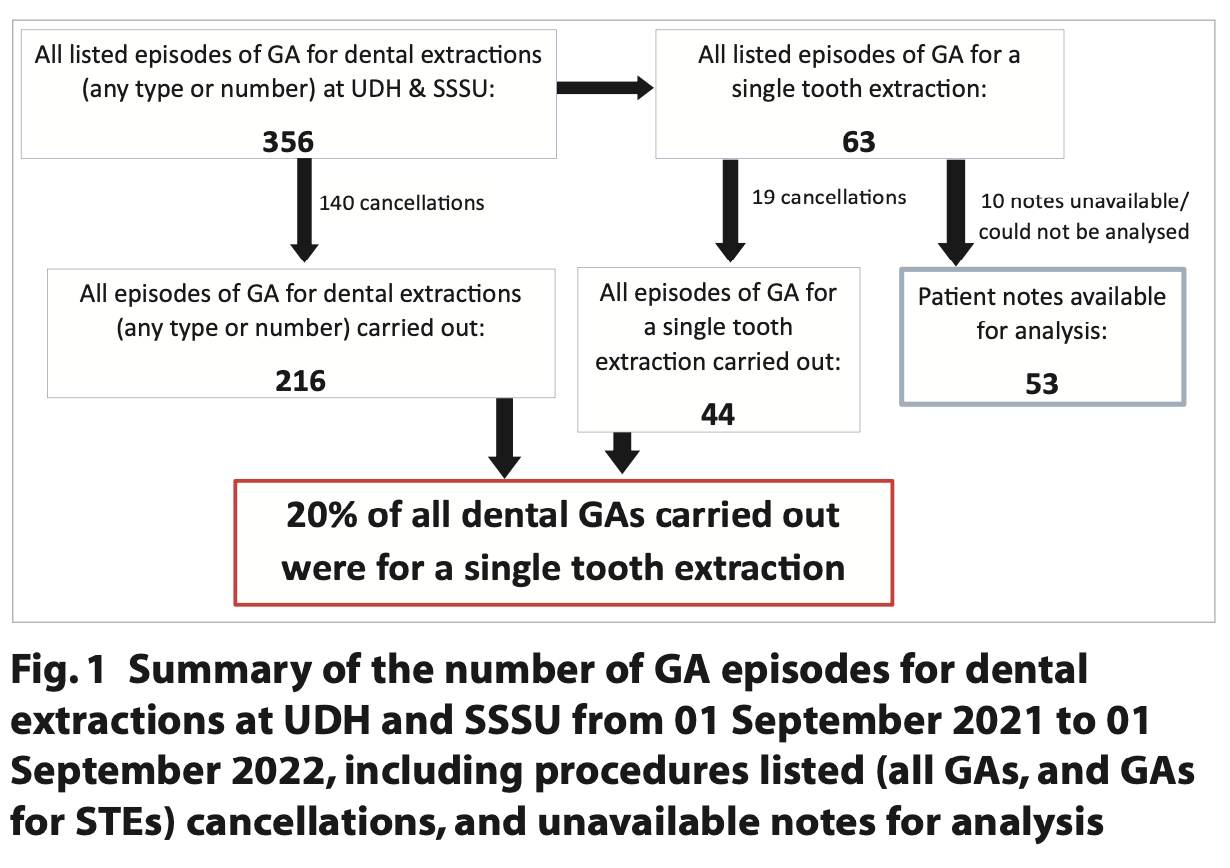

The number and nature of all episodes of extractions under GA between 01 September 2021 and 01 September 2022 across both sites are shown schematically in Figure 1.

In summary: 356 patients were listed for extractions (of any number / type) under GA across the two sites (SSSU n=114; UDH n=242). 140 episodes were cancelled. 63 episodes of STE under GA (meeting the inclusion criteria) were scheduled. Of these, 10 patient files were unavailable for analysis and consequently excluded. Of the 216 GAs for dental extractions, 44 were for STEs (20%). Reasons cited for late notice cancellation included ‘appointment inconvenient’ (14%), ‘medically unfit for surgery’ (13%), ‘pre-operative instructions not followed’ (11%), ‘patient unwell’ (6%) and ‘operation not wanted’ (6%) as well as hospital-based cancellations due to staff sickness, theatre space and emergencies.

Demographics

1.8x more females underwent STEs under GA than males. The age of patients ranged from 18 to 74 with the average age being 36.7 years.

Procedure undertaken

The most common procedure undertaken was the removal of third molars (38%). The next most common procedure was the removal of molars (28%), followed by extractions with management of cysts (15%), premolars (9%), then incisors and canines (6%). Less common procedures included surgical removal of supernumerary teeth (2%) and exposure and bonding of a gold chain to impacted teeth (2%).

Complexity of procedure

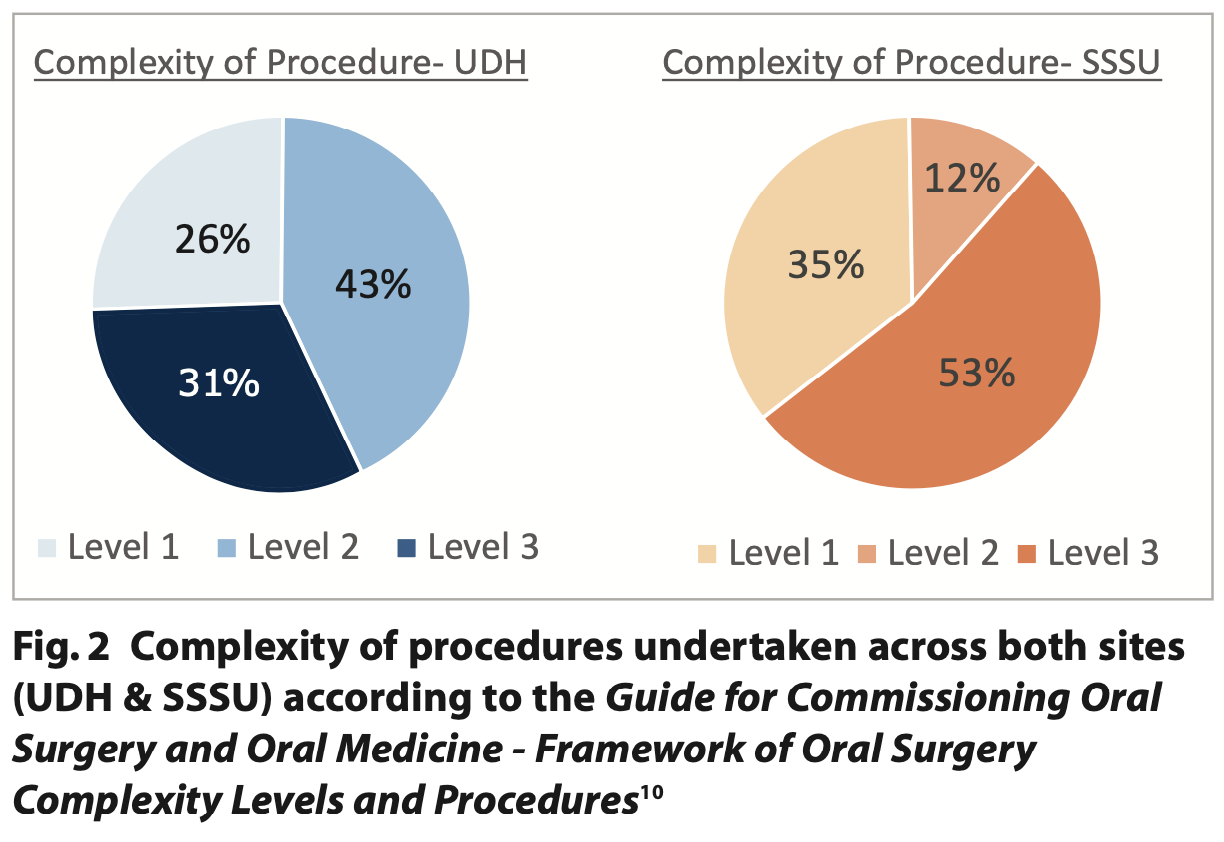

Across both sites (UDH & SSSU) 29% of STEs were listed for level 1 procedures, 33% were for level 2 and 38% were for level 3 procedures.

When comparing the complexity of procedures carried out between the two sites, it was found that a higher percentage of level 3 procedures were carried out in SSSU compared to UDH (Fig. 2).

Referral to treatment (RTT) time and length of operation

The mean waiting time for a STE from referral to the date of the GA was 84 weeks for an operation which lasted an average (mean) of 47 minutes, including anaesthesia.

At UDH, RTT times ranged from 6 weeks to 152 weeks with the mean and median waiting times being 62 weeks and 50 weeks respectively. Comparatively at SSSU, there was a larger range of waiting times from 4 four weeks to 268 weeks, with patients waiting longer on average for their procedure (mean RTT = 105 weeks and median RRT = 121 weeks). The length of the operation, including anaesthesia, ranged between 23 and 74 mins (UDH) and 40 and 60 mins (SSSU). Unfortunately, it was not possible to record the length of the procedure itself or ‘knife-to-skin time’ due to completeness of operation notes.

Reason for STE under GA

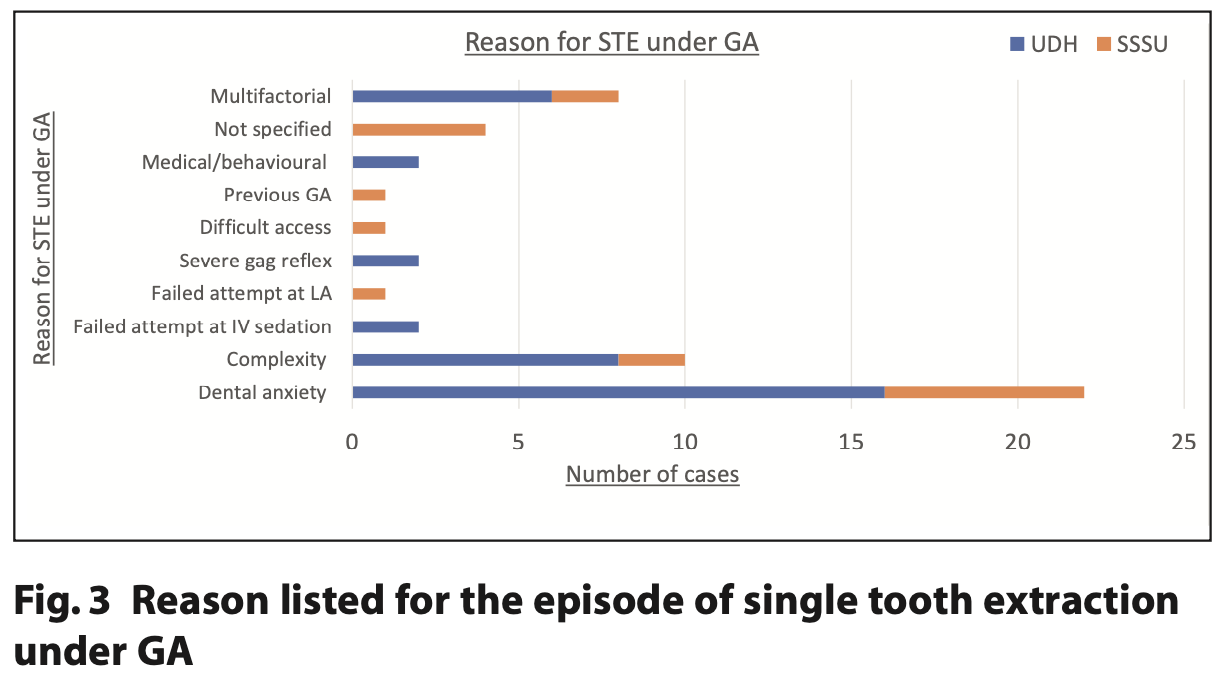

The exact words used by clinicians when justifying the episode of GA varied greatly, so for the purposes of this study, the reasons for listing were categorised according to common themes. Categories included: dental anxiety; procedural complexity; difficult access; medical / behavioural; severe gag reflex; failed attempt at LA; failed attempt at intravenous sedation (IVS); previous GA and multifactorial (for cases which cited more than one of the above reasons).

The most common reason for the listing of a STE under GA was dental anxiety (Fig. 3), with many cases specifically stating patient-demand or preference as the reason. The next most common justification was procedural complexity. Only a small percentage of the cohort were listed for GA due to failure of other treatment modalities including extractions under LA (4) or IVS (2).

Breakdown of the multifactorial category showed that ‘dental anxiety and procedural complexity’ was the next most common justification (4). Other combinations included anxiety + failed attempt at LA (1), difficult access + complexity (1), failed attempt at LA + complexity (1) and failed attempt at LA+ complexity + severe gag reflex’ (1).

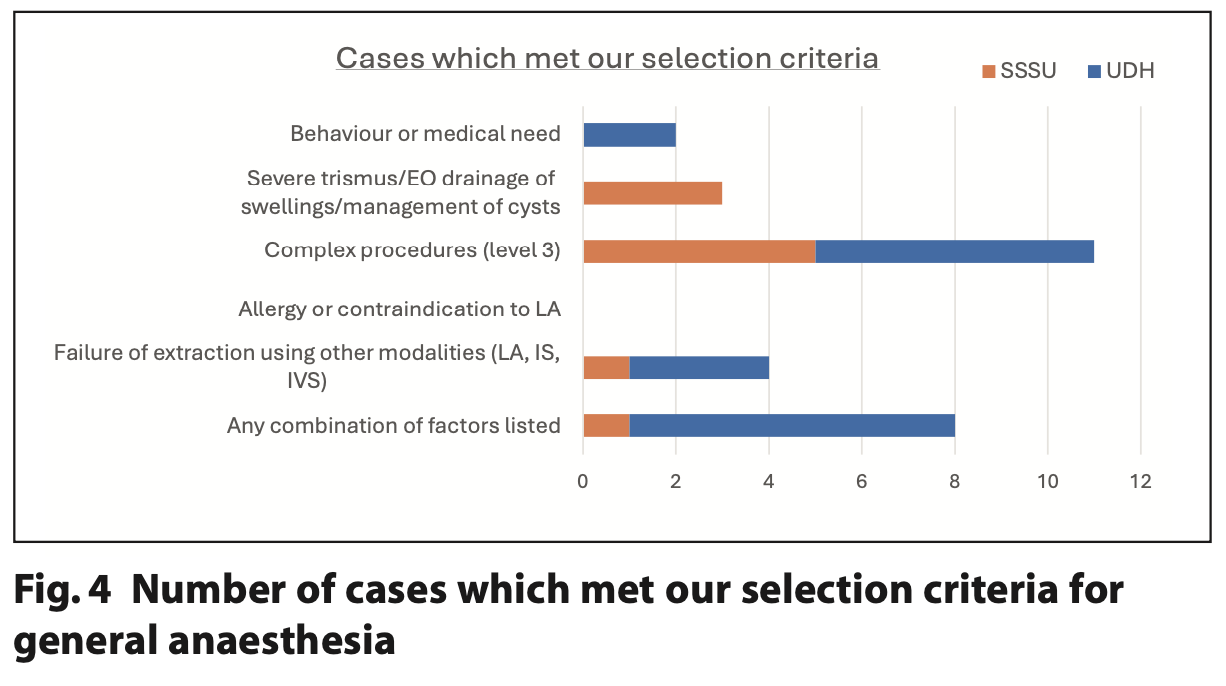

Cases meeting the selection criteria

28 cases met the case selection criteria established for this study as illustrated in Figure 4. However, since the Modified Dental Anxiety Score (MDAS) was not recorded in any of the cohorts’ notes, the extent of patient anxiety was not measurable and was therefore excluded from this analysis. Consequently, the remaining 25 cases did not satisfy our proposed criteria for GA, representing 36% of STE cases and 7% of all GA cases. It's important to note that the absence of MDAS data may result in these percentages being overstated.

Was sedation offered?

Conscious sedation was not offered or not recorded in 62% of the cases. None specifically stated that sedation was not suitable. However, this may be inferred by the context of the procedure undertaken, its relative complexity and recorded reason for the listing of GA.

Previous experience of dental treatment without GA?

The vast majority (73%) of patients had previously tolerated some form of dental treatment without GA, however, it was not possible to distinguish what types of dental treatment this encompassed as this information was often not recorded.

Previous experience of dental GA?

12% of patients had previous experience of dental GA.

Discussion

The principal finding from this study was that a significant proportion of dental GAs carried out were for STEs, the majority of these listed due to dental anxiety. The relative simplicity of many of the procedures within this cohort and lack of medical / behavioural indicators make it difficult to justify from a clinical perspective.

A survey showed that clinicians believed the main factor influencing whether treatment should be carried out under GA was failure of previous attempts to carry out treatment using alternative anaesthetic modalities. However, when the same clinicians were asked about the proportion of adults listed for GA due to a failure of sedation, most clinicians perceived this proportion to be small, instead identifying dental anxiety being the main reason.3 These findings are in keeping with the results of this study.

Many factors are likely to contribute to the increased demand for extractions under GA:3,8

- Barriers to alternative anaesthetic modalities: availability of sedation services, staff training and lack of time for clinicians to counsel an anxious patient

- Lack of specific guidance or selection criteria for GA

- Poor remuneration for difficult exactions or managing anxious patients in primary care

- Ignorance at a primary care level for true clinical justification for GA

- Clinician and patient perception that severe anxiety is a barrier to attempt treatment under LA.

Also important to note are the high number of cancellations. Treatment under GA relies on multiple factors including in-date pre-operative assessments, clerking patients and multiple members of staff (anaesthetist, surgeon, scrub team, operating department practitioners, recovery staff etc). Disruption to any stage of this process may result in a cancellation. The timeframe for the study was post COVID-19, so it is likely that staff illness could be a contributing factor. In comparison, dentist-led IVS relies on far fewer factors so could be considered more resilient to cancellations.

Recommendations

Conscious sedation is a safer and cheaper alternative to GA and discussions about all treatment modalities should be promoted between the clinician and patient. Comprehensive discussion about all relevant anaesthetic options including the clinician’s reasoning about their recommendation has been shown to influence the patient’s decision about their choice for GA.12

Although several drugs exist for conscious sedation in dentistry, each have limitations. Ketamine is considered an advanced sedation technique requiring administration by a dedicated sedationist and there are no guidelines for its use due to limited evidence around its safety and efficacy.13 Propofol (requiring anaesthetist-led sedation or dedicated anaesthetist / sedationist) delivered by target-controlled infusion has a narrow therapeutic index and reduced safety margin which could increase the likelihood of adverse events.13,14 Due to being reliant on staffing, training and skills in use of advanced techniques is somewhat limited.

Titrated IV midazolam has an excellent efficacy and safety record and is approved for use in primary care settings.13,14 However, its relatively slow onset and high incidence of post-operative adverse reactions are notable drawbacks.15

Remimazolam is a novel, ultra-short acting benzodiazepine which has been approved for use in the UK in 2023 by the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry as a safe and effective alternative to IV midazolam.16 Remimazolam has a faster onset, more rapid recovery and lower incidence of post-operative side effects compared to midazolam, resulting in higher patient satisfaction.15 Although the cost of an ampule of remimazolam is greater than that of midazolam,17,18 micro-cost analysis of the entire patient journey showed remimazolam to be more cost-effective, with the main driver of savings being attributed to the reduced recovery phase.19 While IV midazolam is effective for most patients, the introduction of remimazolam may provide a valuable alternative treatment option for STEs.

NHS England have recently suggested a model of dental anxiety management outlining which technique(s) should be utilised according to the level of anxiety, urgency and invasiveness of treatment, including any co-morbidities. These guidelines recommend that patients should be managed with the simplest and safest technique which is likely to be successful. GA should be limited to patients who can’t be managed with sedation due to true phobia, complex or numerous procedures or a medical contraindication.20 Some NHS Trusts in the UK have also developed their own strict acceptance criteria for GA referrals,21 however, other units have reported formal complaints from patients who were told that a GA was clinically inappropriate.3 Specific GA selection criteria at a national level are required.

Furthermore, greater responsibility should be placed on the referring dentist and the clinician listing the patient for GA to demonstrate active exclusion of other treatment modalities before GA is considered.

Conclusion

Data from this study represents one UK-based secondary care department, meaning limited conclusions can be drawn. The finding that 20% of all GAs carried out over a 12-month period were for a STE raised many discussion points including the need for appropriate utilisation of the existing sedation services available. The long-term management of these patients should be considered as GA does not improve dental anxiety and it is likely that this cohort will experience repeat GAs unless our professional approach changes. A clear distinction is required between the terms ‘patient requests GA’ and ‘patient requires GA’, particularly considering the financial and resource-based pressures the NHS currently faces.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

1. Public Health England. Hospital tooth extractions of 0 to 19 Year Olds. 2019. Online information available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hospital-tooth-extractions-of-0-to-19-year-olds (accessed June 2023).

2. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Guideline for the Use of General Anaesthesia (GA) in Paediatric Dentistry. RCSENG; 2008. Davies C, Harrison M, Roberts G. Online information available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/fds/publications/guideline-for-the-use-of-ga-in-paediatric-dentistry-may-2008-final.pdf https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/fds/publications/guideline-for-the-use-of-ga-in-paediatric-dentistry-may-2008-final.pdf (accessed June 2023).

3. Hong B, Baker A. General anaesthetic service for adult dental extractions: an 'À La Carte Menu'? Survey results. Br Dent J 2017; 24;222: 261-7.

4. General Dental Council. Standards for the dental team. 2013. Online information available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/standards-guidance/standards-and-guidance/standards-for-the-dental-team (accessed May 2023).

5. Pike D. A conscious decision. A review of the use of general anaesthesia and conscious sedation in primary dental care. SAAD Digest 2000; 1;17: 13-4.

6. Common events and risks in anaesthesia. Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2019. Online information available at https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2021-12/Risk-infographics_2019web.pdf (accessed June 2023).

7. Fox F, Whelton H, Johnson O A, Aggarwal V R. Dental Extractions under General Anesthesia: New Insights from Process Mining. JDR Clinical & Translational Research 2023; 8: 267-275.

8. Hong B, Birnie A. A retrospective analysis of episodes of single tooth extraction under general anaesthesia for adults. Br Dent J 2016; 15;220: 21-4.

9. Jameson K, Averley P A, Shackley P, Steele J. A comparison of the 'cost per child treated' at a primary care-based sedation referral service, compared to a general anaesthetic in hospital. Br Dent J 2007; 22;203: 13

10. Oral surgery clinical standard. NHS England. 2023. Online information available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/oral-surgery-clinical-standard/ (accessed June 2023)

11. Coulthard, P. The indicator of sedation need (IOSN), Dental Update 2013. 40(6), 466–471.

12. Tyrer G L. Referrals for dental general anaesthetics—how many really need GA? Br Dent J 1999; 187: 440-4.

13. Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care (V1.1): Report of the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. RCS Publications, 2020.

14. Conscious Sedation in Dentistry. Dental clinical guidance. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) 2017.Online information available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/media/iota3oqm/sdcep-conscious-sedation-guidance-unchanged-2022.pdf (accessed June 2023).

15. Li X, Tian M, Deng Y, She T, Li K. Advantages of Sedation with Remimazolam Compared to Midazolam for the Removal of Impacted Tooth in Patients With Dental Anxiety. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023; 1;81: 536-45.

16. Remimazolam for intravenous conscious sedation for dental procedures IACSD standard on clinical use and training. RCSENG. 2023. Online information available at https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/fds/iacsd/iacsd-remimazolam-statement-090123-final.pdf (accessed June 2023).

17. Midazolam Medicinal Forms. British National Formulary (BNF). 2023. Online information available at https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/midazolam/medicinal-forms/#solution-for-injection (accessed June 2023).

18. Remimazolam Medicinal Forms. British National Formulary (BNF). 2023. Online information available at https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/remimazolam/medicinal-forms/#powder-for-solution-for-injection (accessed June 2023).

19. Pedersen M H, Danø A, Englev E, Kattenhøj L, Munk E. Economic benefits of remimazolam compared to midazolam and propofol for procedural sedation in colonoscopies and bronchoscopies. Current medical Research and Opinion 2023; 4;39: 691-9.

20. Clinical guide for dental anxiety management. NHS England. 2023. Online information available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/clinical-guide-for-dental-anxiety-management/ (accessed June 2023).

21. General anaesthesia acceptance criteria. Barts Health NHS Trust. 2023. Online information available at https://dental.bartshealth.nhs.uk/general-ana (accessed June 2023).