Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

The effectiveness of dental nurse led Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) on the dentally anxious patient:

a service evaluation

K. Kauser BDS, BMedSci*1

S. Naidu BDS2

R. Jaffery BDS, MFDS RCS Edin, PG Dip Cons Sed, MSc (Rest Dent)3

1Speciality Trainee Registrar

2Senior Dental Officer

3Senior Dental Officer, Special Care Dentistry, Birmingham Community Healthcare Trust, Birmingham Dental Hospital, 5 Mill Pool Way, Birmingham, B5 7EG

*Correspondence to: kiren.kauser@nhs.net

Kauser K, Naidu S, Jaffery R. The effectiveness of dental nurse led Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) on the dentally anxious patient: a service evaluation. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 42-46

Abstract

Introduction

Dental Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (dental CBT) is a talking therapy for adults and children aimed to reduce a patient’s anxiety specifically related to dentistry. The Modified Dental Anxiety Score (MDAS) allows an objective measurement of the patient’s level of anxiety pre and post CBT.

Aims

The objective was to assess the effectiveness of the CBT service within Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (BCHC) Community Dental Services (CDS). The aims were to assess the number of patients with a pre- and post-CBT MDAS recorded, the success of CBT and the anxiety management modalities used to facilitate treatment.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of internal CBT referrals between January 2018 to December 2022.

Results

135 referrals were identified. 56% had a pre-MDAS score, of these 85% were between 20 to 25, indicating high anxiety (>19). Post-CBT MDAS scores reduced to between 5 to 14 for 85% of patients (indicating low / moderate anxiety). After having CBT 45% of patients had dental treatment with local anaesthetic (LA) alone and 35% with inhalation sedation (IHS).

Conclusions

CBT is effective in the treatment of dental anxiety and therefore allows patients to receive treatment from their general dental practitioners (GDP) and step down from general anaesthetic (GA) / intravenous sedation (IVS).

Introduction

Dental anxiety is common within the UK and is a known barrier to dental care.1 The Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 suggested that 51% of adults in the UK have low level dental anxiety, 36% have moderate and 12% have extreme dental anxiety indicative of possible dental phobia.2 Additionally, a higher proportion of patients with a high level of anxiety have not visited the dentist for the last ten years (24%) compared to those who visited within the last 12 months (9%) which suggests high level anxiety is associated with avoidance behaviours.2-4

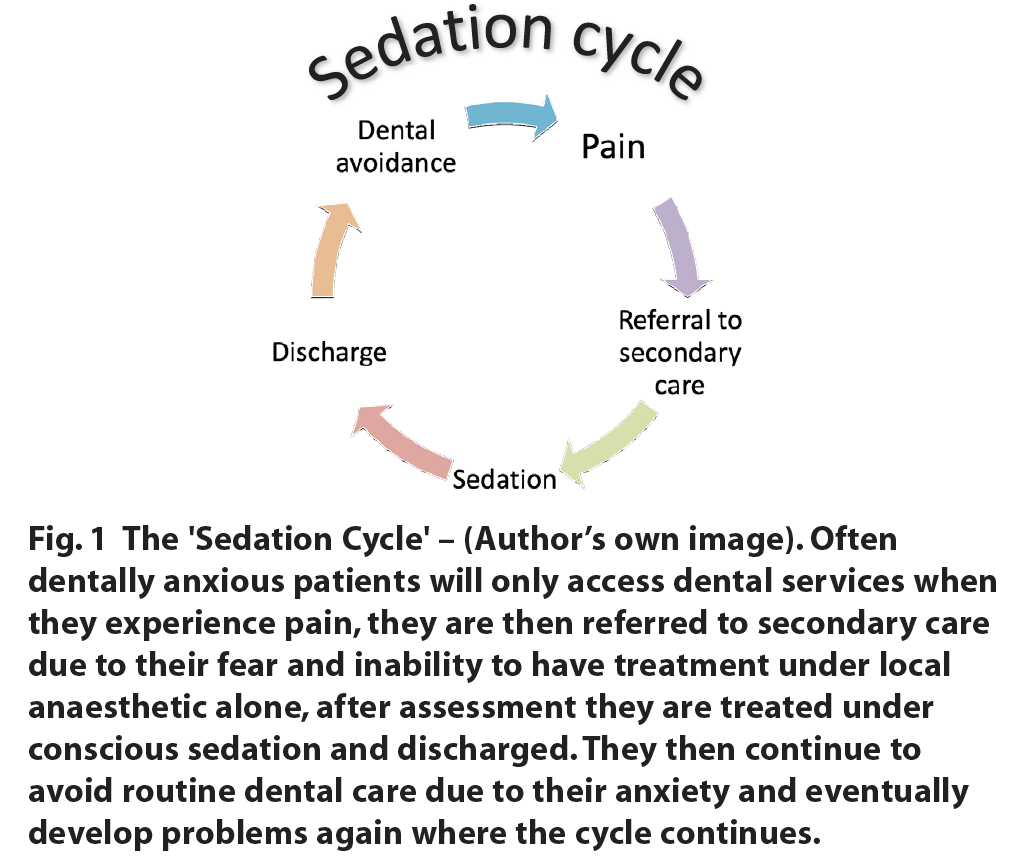

GDPs will typically refer anxious patients for sedation to receive the dental treatment they require. However, this does not always help these patients to reduce their anxiety, resulting in a reliance on sedation for future care. This can be illustrated by the ‘sedation cycle’ (Figure 1). As there has been no intervention to help overcome their anxiety, unfortunately the cycle continues, where again they may avoid routine care until pain strikes.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a short term talking therapy which has been shown to help those with anxiety-related disorders.5 CBT has been well recognised and advocated by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of specific phobias.6 The recently published Clinical Guide for Dental Anxiety Management highlighted CBT as a treatment modality for those with high level dental anxiety.7 The guidance details that the aim of CBT is to reduce the anxiety in these individuals with the goal for the patient to be seen in primary care by tier one and two practitioners.7 Furthermore, it advocated CBT to aid the delivery of dental care to the patient, as well as providing a long term cure of dental anxiety for the patient.7

There is a strong evidence base supporting the use of CBT. A randomised control trial showed that a short course of CBT delivered to dentally anxious patients immediately after assessment, and to those delayed by four to six weeks, showed a significant difference in the reduction of dental fear in both groups.8 This reduction was still present after a two year follow up, showing the effects of the CBT brief intervention had a positive long-lasting effect.8

A service evaluation by Kani, Asimakopoulou and Daly et al., in the UK looked at the outcomes of patients referred to a CBT service for their dental anxiety.9 A total of 111 patients were referred, 77% with a Modified Dental Anxiety Score (MDAS) score indicating dental phobia. 103 patients (93%) were treated without the use of sedation. 19 patients (15%) did not complete their course of CBT as they were not suitable or opted out.9 This service evaluation shows that many of the patients who attended dental CBT were then able to have dental treatment carried out without the need for repeat sedation.9

The CBT service at Birmingham Community Healthcare (BCHC) Community Dental Service (CDS)

A significant proportion of patients referred to the BCHC CDS Anxious Adult service are repeat referrals.

The BCHC Dental CBT service can address generalised dental anxiety, needle phobia and those with a prominent gag reflex. The therapy is provided by specially trained dental nurses. The case load is supervised by a psychologist, and the service supported by clinicians as part of a multidisciplinary team (MDT).

The CBT identifies the negative thought patterns and beliefs leading to the negative feelings, actions and behaviours. A variety of clinical methods and exercises are undertaken such as graded exposure or systemic desensitisation, acclimatisation, breathing and relaxation aimed at increasing trust and control.

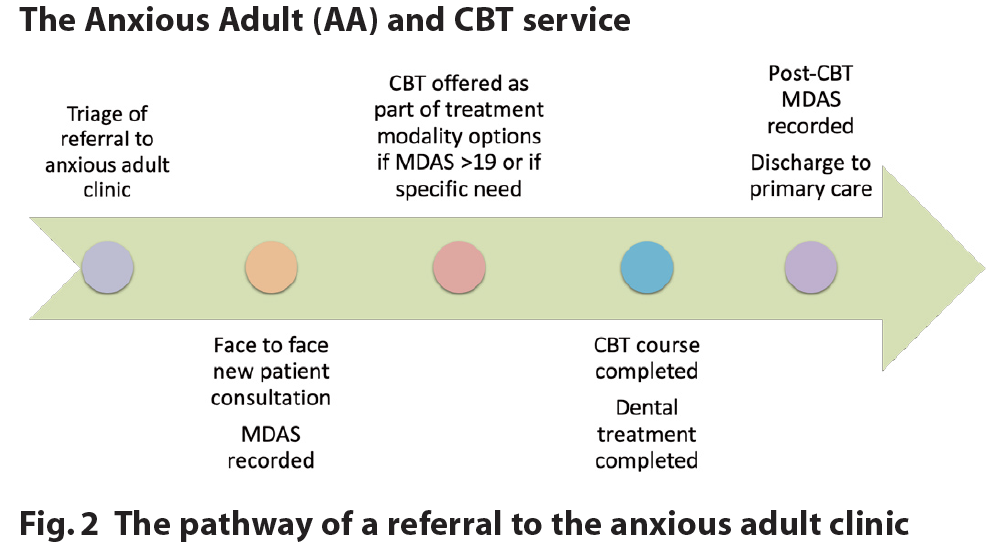

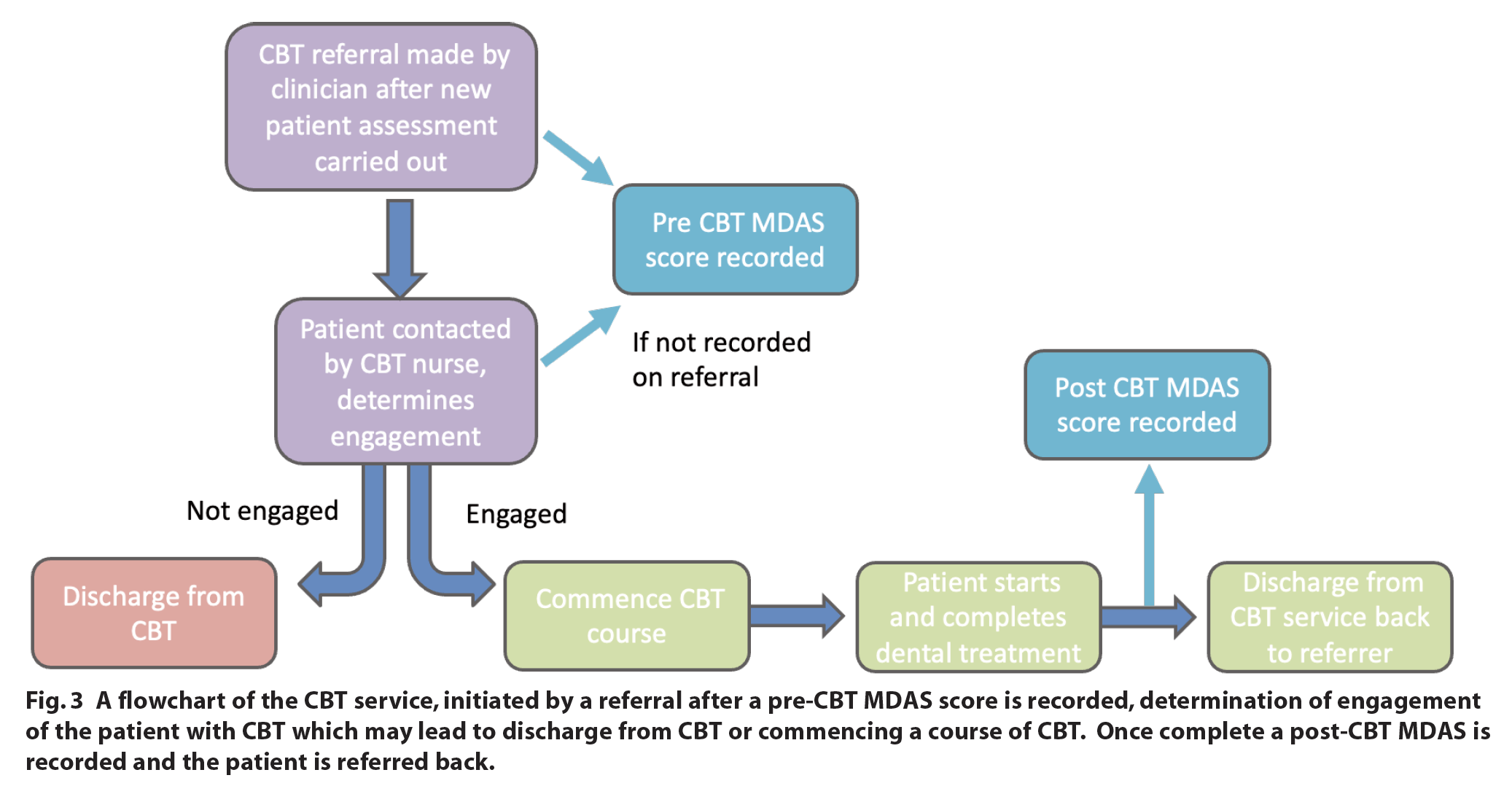

Once a referral has been received, following a period on the waiting list, the patient is invited for a consultation. The level of the patient’s anxiety is determined by recording a MDAS (Figure 2). The MDAS tool, part of the Indication of Sedation Need (IOSN) is a simple screening tool for dental anxiety.10 It consists of five brief multiple-choice questions asking how anxious a patient would feel in five dental-related scenarios.10 For patients with learning disability, the child MDAS can be used instead which uses face symbols instead of words. The answer choices range from not anxious (a score of one) to extremely anxious (a score of five). The scores are summed to give an overall indication of the patient’s level of anxiety. This results in a score ranging from five to 25, with scores of 19 and above indicating high level dental anxiety.10 This score helps indicate to the clinician those with significantly high levels of anxiety to warrant CBT intervention.7 The patient is subsequently offered CBT as part of their treatment options (Figure 2). If the patient wishes, an electronic internal referral to the CBT service is made (Figure 3). A CBT nurse will further triage, via telephone, the patient’s anxiety, motivation and expectations prior to commencing face to face sessions in a non-clinical or clinical setting, lasting between six and ten sessions. Virtual therapy via video platforms may open access in the future, however, currently is not offered within the service.

Once the CBT and dental treatment is completed, a post-CBT MDAS is recorded to help determine whether CBT helped to reduce the patient’s level of dental anxiety (Figure 3).

Objective and aims of the service evaluation

The objective of the service evaluation was to establish the effectiveness of CBT for the dentally anxious patients within BCHC CDS:

- To assess the recording of an initial MDAS on referral

- To assess the number of patients who have a post treatment MDAS recorded

- To infer the effectiveness of CBT via reduction in MDAS and the treatment modalities used for dental treatment.

Materials and methods

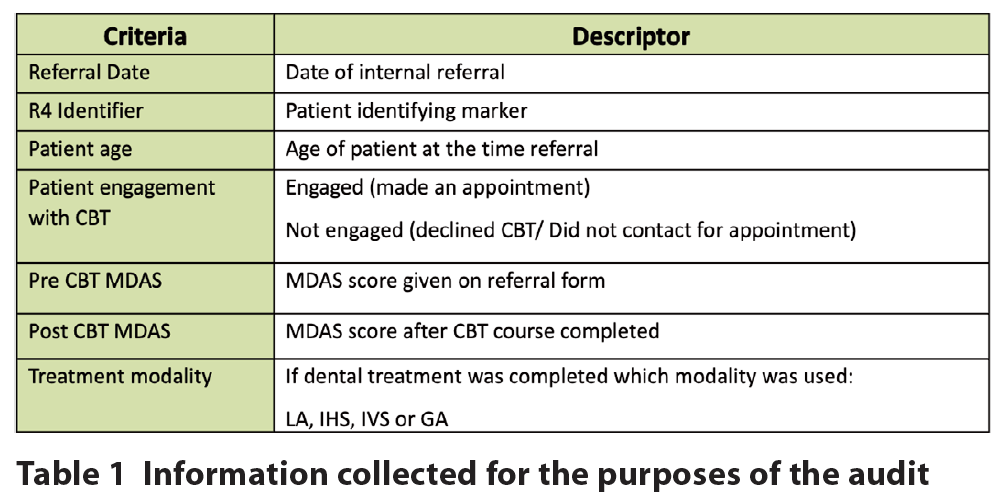

A five-year retrospective analysis of all internal CBT referrals within the service between January 2018 and December 2022 was made. A contemporaneous database of referrals received, and their outcomes, had been maintained since the establishment of the CBT service. This was utilised for data collection alongside the patient’s electronic clinical notes (Table 1).

The inclusion criteria for the audit were: internal referrals made to the CBT service and the CBT and dental treatment were completed between January 2018 and December 2022. The exclusion criteria were external referrals (not following a standard referral process), as well as patients whose CBT or dental treatment was not completed.

Results

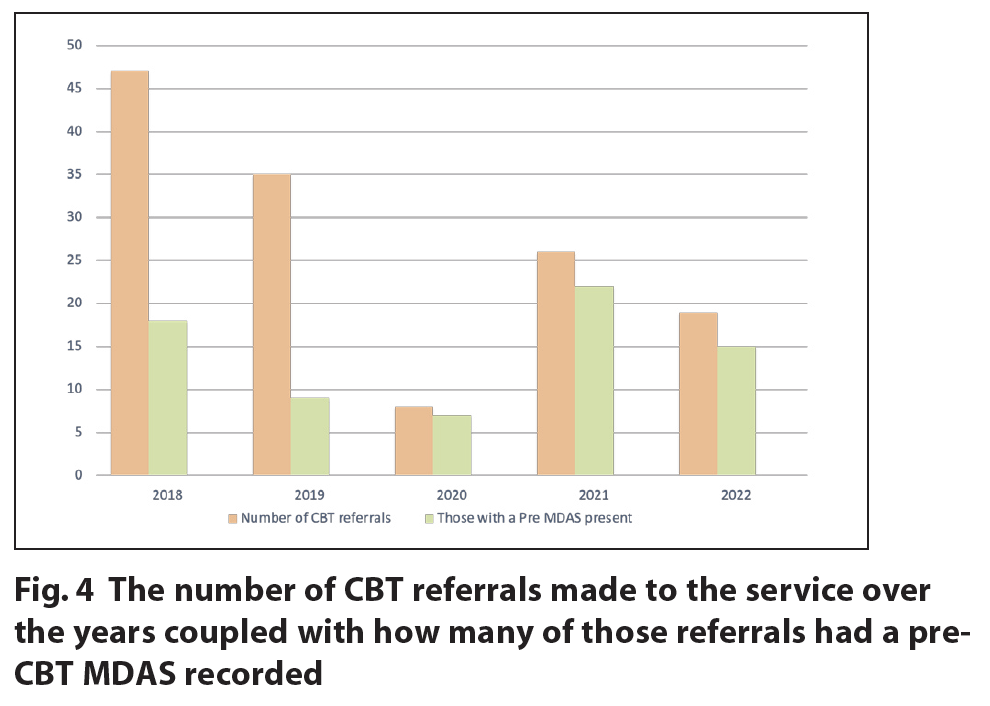

138 referrals met the inclusion criteria. The annual number of referrals is illustrated below (Figure 4). The greatest number of referrals (34%) made was during 2018, (n = 47) however, only 38% of the referrals had a pre-CBT MDAS present which reduced further in 2019 to 26%. However, from 2020 onwards there has been a significant improvement in the recording of a pre-CBT MDAS which increased to 88% in 2020, 85% in 2021 and 79% in 2022. Notably there has been a reduction in referrals overall to the service over the years, due to the loss of CBT-trained dental nurses without replacement following the COVID-19 pandemic.

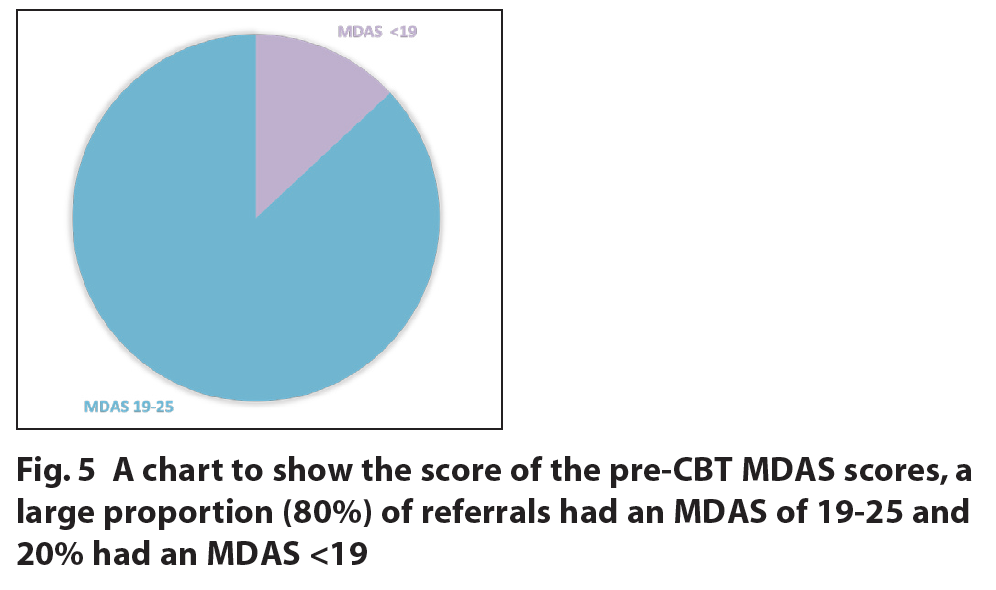

The score of the pre-CBT MDAS in most cases (80%) was greater than 19 indicating severe dental anxiety / phobia (Figure 5). 20% of the referrals had a MDAS less than 19. In such cases the patients had a specific anxiety such as a severe gag reflex or needle phobia.

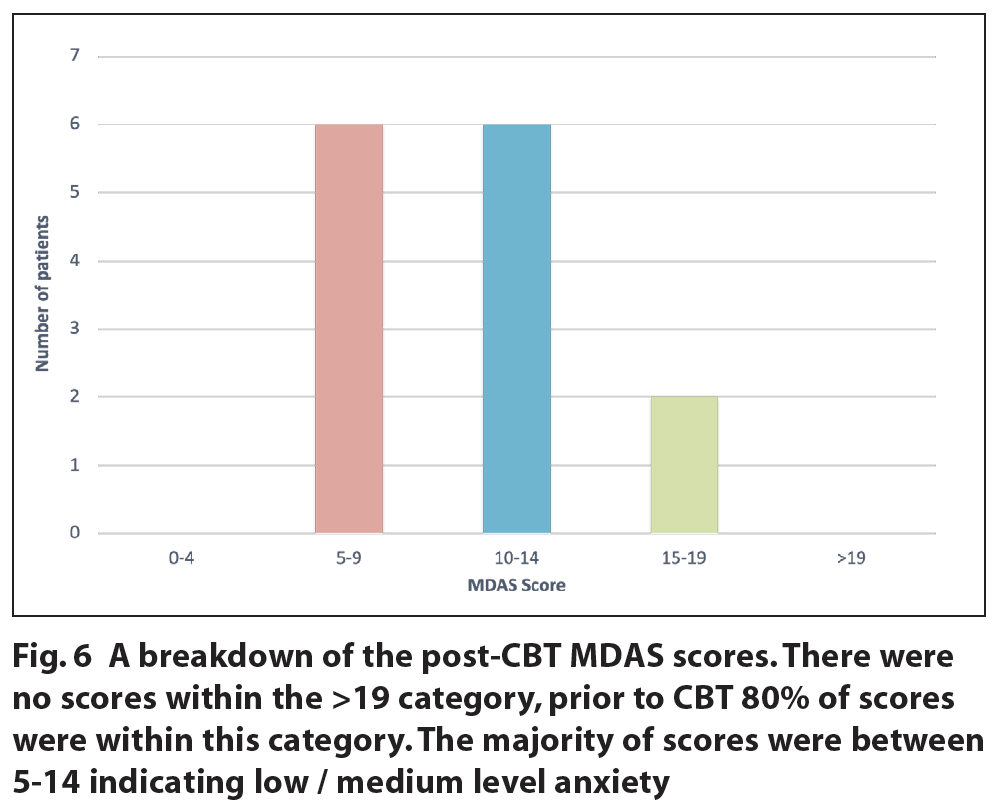

Upon completion of CBT, a post-CBT MDAS was recorded. Unfortunately, only 19% of referrals, which also had a pre-MDAS recorded (80% of the total sample), had a post-CBT MDAS recorded (Figure 6). No patients had a score of more than 19 after CBT intervention (80% of pre-CBT score were >19), this indicates that CBT was able to reduce high levels of anxiety. 43% of scores were between 10 and 19 and 43% were also between 5 and 9.

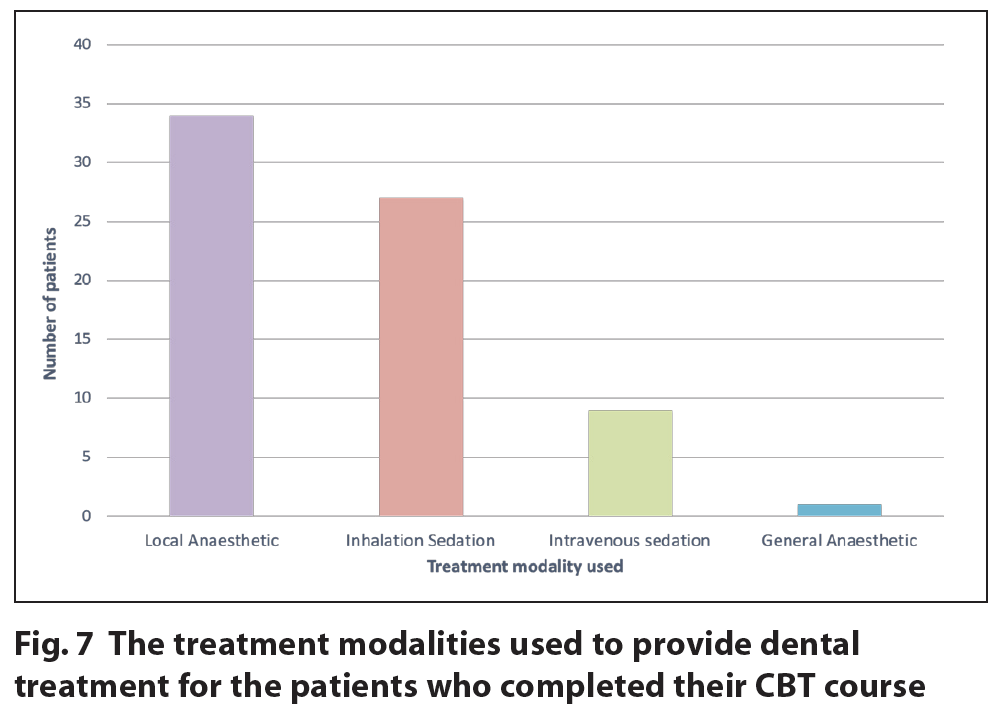

Finally, the treatment modalities used to provide dental treatment for the patients who had completed a course of CBT were assessed (Figure 7). The treatment modalities ranged from LA (48%) alone, conscious sedation: IHS (38%) or IVS (13%) or GA (1%) of the total sample.

Discussion

This service evaluation aimed to assess the recording of pre- and post-MDAS scores for patients on their CBT journey and to infer the effectiveness of the current CBT service in reducing patients’ level of dental anxiety shown by a reduction in MDAS scores. An additional aim was to identify which treatment modalities were used to provide dental treatment for patients following a course of CBT.

The recording of MDAS scores

The recording of a pre-MDAS has improved over the years ranging from 26% to 88%, however, this service evaluation highlighted the need to improve staff awareness of the referral process, as many internal referrals lacked the recording of the pre-CBT MDAS, which is a criterion for CBT referral. Due to the size of the dental division at BCHC and with new staff and trainees, annual training on the CBT pathway and referral process would be beneficial and aid the increase in recording of pre-MDAS scores upon referral, as well as act as a refresher for all staff.

It was identified that only 19% of the referrals made to the CBT service had a post-CBT MDAS recorded. This finding is likely due to the fact that those who have conscious sedation on their final dental treatment appointment did not have their post-CBT MDAS score recorded because recording an MDAS after completion of treatment is not appropriate while under the effect of the sedation.

Usually, a pre-MDAS score is recorded on a paper form prior to referral to the CBT service. If this has not been completed it is then recorded by the CBT nurse over the telephone, where the patient is contacted following a received referral to determine the patient’s engagement with CBT and offer an initial CBT appointment if appropriate. The post-MDAS score is recorded on the last treatment appointment once the dental course of treatment (CoT) has been completed and prior to discharge from the CBT service. This can be problematic if a patient has had conscious sedation on their final treatment appointment as an accurate recording MDAS would not be achieved.

Ways to overcome this barrier have been explored. These include MDAS forms being sent home with the patient to be completed and returned following recovery from the conscious sedation and the patient being contacted via telephone or letter to complete the post-MDAS, all of which have been minimally successful. This unfortunately prevents a broad picture of the effectiveness of CBT to be seen. As a future action the aim will be to consider an alternative electronic survey to capture Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) and post-MDAS as part of a review, an additional appointment following completion of their CoT prior to discharge.

Reduction in anxiety following a CBT course

While a small number of post-MDAS scores were recorded, those included showed a significant improvement in patient outcomes, where dental anxiety was significantly reduced as shown by the decrease in MDAS (pre- and post-MDAS scores) after having CBT. 80% of patients had a high level of dental anxiety prior to CBT and the level of anxiety in all these patients was reduced following CBT. This finding is in line with the current literature which shows that CBT is effective in reducing dental anxiety.11-14 Additionally, the results suggest that following a dental CBT course, patients will be more likely to seek routine dental care from their GDP, as many of the patients were then able to have dental treatment without the need for sedation, supporting the current literature that CBT for dental anxiety encourages regular dental attendance.15-18 The study has shown that CBT is an effective non-pharmacological modality to reduce dental anxiety and step patients down from conscious sedation as well as support those to access IVS where anxiety is too great.

Stepping down to non-sedation

The results show that most patients were treated using LA only or inhalation sedation. Although patients stepping down to non- sedation was not directly explored, inferences can be made that patients are being empowered to step down from IVS and GA as they address their dental anxiety with CBT. This can enable these previously phobic patients (MDAS >19) to obtain dental treatment from their GDP under LA alone in some cases. This will in turn enable patients’ dental disease to be prevented or managed as and when it has been diagnosed by GDPs, avoiding lengthy delays on waiting lists. This benefits the patient by reducing their pain experience and achieving stable oral health sooner, and benefits the CDS by reducing pressures on sedation services. Waiting lists are shortened which results in improved access for other patients waiting to be seen.

A possible upstream effect for paediatric patients

Although not explored in this service evaluation, it has been shown that dental phobic adults who have, or care for, children can lead to the child becoming dentally anxious or phobic through vicarious learning.20 Overcoming these anxieties in the dentally anxious adult population using CBT should in turn allow a reduction in the paediatric dentally anxious population as an upstream approach.

Implementation of changes

Increase in CBT dental nurses

From 2018 there has been a reduction in the referrals to the service, particularly in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic where the service was running with only one CBT nurse. The region covered was significantly reduced which in turn reduced the capacity of our service. However, the service is now experiencing an increase in referrals.

There has been a drive to recruit and train eight additional dental nurses for the CBT nurse role following the publication of the management of dental anxiety commissioning guidance.7 This in turn will allow greater accessibility for patients and remove this access barrier.

CBT study day

Although the recording of a pre-MDAS had improved over the years ranging from 26% to 88% there was an identified need to improve staff awareness of the CBT service and the referral process. A CBT study day was organised, which discussed the service in depth as well as the criteria for referral and the importance of a pre-CBT MDAS. The CBT referral form was also discussed, to specifically include the pre-MDAS score as its own entity on the form. The CBT MDAS form will be used to standardise internal referrals. This will help to achieve the 100% standard set in this audit. An electronic form containing mandatory fields may also assist with compliance in the future.

Anecdotally, there has been a decrease in re-referrals seen within the service between January 2018 and December 2022. Although a longer time period is required to fully investigate this finding, it is promising.

Increasing post-MDAS recording

To overcome barriers to recording post-MDAS CBT scores, a review appointment will be offered to patients to attend prior to discharge from the service where CBT PROMS and PREMS will be collected as well as the post-MDAS score.

Action plan

A re-evaluation will be completed in 12 months to allow the implementation of the changes and assess compliance with the standards. Furthermore, CBT PROMS and PREMS will allow further refining of the service.

Conclusion

The CBT service is a valuable modality to allow anxious patients to directly access dental care with LA and support for those to access IVS and GA where anxiety is too great.

CBT is a clinical therapeutic approach which addresses the root cause of a patient’s anxiety, equipping them with the skills for many to step off the ‘sedation cycle’, overcome dental avoidance and allow routine visits to their GDP for prevention and treatment as and when required. CBT as part of non-pharmacological behavioural management should be considered a mainstay of treatment for suitable dental phobic patients to help provide a long term ‘cure’ for their fear / anxiety. The ultimate benefit is for the patient, but this will also benefit services and the wider community in accessing dental care.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Jacqueline Green, senior CBT dental nurse, for her expertise and guidance with this service evaluation.

References

1. Milgrom P, Newton J T, Boyle C, Heaton L J, Donaldson N. The effects of dental anxiety and irregular attendance on referral for dental treatment under sedation within the National Health Service in London. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010; 38: 453-9.

2. NHS Digital. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 – Theme 8 Access barriers to care. Online information available at https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub01xxx/pub01086/adul-dent-heal-surv-summ-them-the8-2009-re10.pdf (accessed July 2023).

3. Schuller A A, Willumsen T, Holst D. Are there differences in oral health and oral health behavior between individuals with high and low dental fear?. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003; 31: 116-21.

4. Armfield J M, Slade G D, Spencer A J. Dental fear and adult oral health in Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009; 37: 220-30.

5. Kaczkurkin A N, Foa E B. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:337-346.

6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults, Clinical guideline: CG113, 2020. Online information available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113/resources/generalised-anxiety-disorder-and-panic-disorder-in-adults-management-pdf-35109387756997 (accessed July 2023).

7. NHS Digital. Clinical guide for dental anxiety management 2023. Online information available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/clinical-guide-for-dental-anxiety-management/ (accessed July 2023).

8. Spindler H, Staugaard S R, Nicolaisen C, Poulsen R. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of a brief cognitive‐behavioural intervention on dental fear. J Public Health Dent. 2015; 75: 64-73.

9. Kani E, Asimakopoulou K, Daly B, Hare J, Lewis J, Scambler S, Scott S, Newton J T. Characteristics of patients attending for cognitive behavioural therapy at one UK specialist unit for dental phobia and outcomes of treatment. Br Dent J. 2015; 219: 501-6.

10. Humphris G, Morrison T, Lindsay S J. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: UK norms and evidence for validity. Comm Dent Health. 1995; 12: 143-50

11. Kvale G, Berggren U, Milgrom P. Dental fear in adults: a meta‐analysis of behavioural interventions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004; 32: 250-64.

12. Wide Boman U, Carlsson V, Westin M, Hakeberg M. Psychological treatment of dental anxiety among adults: a systematic review. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013; 121:225-34.

13. Gordon D, Heimberg RG, Tellez M, Ismail AI. A critical review of approaches to the treatment of dental anxiety in adults. J Anxiety Disord. 2013; 27: 365-78.

14. Getka E J, Glass C R. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to the reduction of dental anxiety. Behavior Therapy. 1992; 23: 433-48.

15. De Jongh A D, Muris P, Ter Horst G, Van Zuuren F, Schoenmakers N, Makkes P. One- session cognitive treatment of dental phobia: preparing dental phobics for treatment by restructuring negative cognitions. Behav Res Ther. 1995; 33: 947-54.

16. Berggren U, Hakeberg M, Carlsson S G. Relaxation vs. cognitively oriented therapies for dental fear. J Dent Res. 2000; 79: 1645-51.

17. Willumsen T, Vassend O, Hoffart A. A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and nitrous oxide sedation in the treatment of dental fear. Acta Odont Scand. 2001; 59: 290-6.

18. Willumsen T, Vassend O, Hoffart A. One-year follow-up of patients treated for dental fear: effects of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and nitrous oxide sedation. Acta Odont Scand. 2001; 59: 335-40.

19. Smith P A, Freeman R. Remembering and repeating childhood dental treatment experiences: parents, their children, and barriers to dental care. Int J Paed Dent. 2010; 20: 50-8.

20. Coric A, Banozic A, Klaric M, Vukojevic K, Puljak L. Dental fear and anxiety in older children: an association with parental dental anxiety and effective pain coping strategies. J Pain Res. 201: 515-21.