Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Are we providing an effective sedation service? An evaluation of a new conscious sedation service in primary special dental care

C. Boynton MA (Hons), BDS (Lond), MJDF (RCSEng), MSc, MSCD, PG Cert*1

S. Harford BDS, MFDS (RCSEd) PGCert (Sed, Oral Surg), MSCD2

S. Spence BDS, MJDF (RCSEng), PG Dip (Sed), MSc, MSCD3

1Consultant in Special Care Dentistry, Royal Devon University Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Exeter Dental Access Centre, Royal Devon and Exeter Hospitals (Heavitree), Gladstone Road, Exeter, EX1 2ED

2Specialist in Special Care Dentistry, Wiltshire Community Dental Hospital, Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Marlborough Road, Swindon, SN3 6BB

3Specialist in Special Care Dentistry, Somerset NHS Foundation Trust, Special Care Dentistry Department, Dorset County Hospital, Williams Avenue, Dorchester, DT1 2JY

*Correspondence to: Camilla Boynton

Email: camilla.boynton@nhs.net

Boynton C, Harford S, Spence S. Are we providing an effective sedation service? An evaluation of a new conscious sedation service in primary special dental care. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 28-32

Abstract

Conscious sedation using midazolam can be an effective primary care dental treatment modality for patients with both dental anxiety and additional needs. This retrospective service evaluation aims to assess the efficacy of conscious sedation with midazolam in a new special care primary dental service, by identifying whether midazolam provided operating conditions sufficient to allow planned dental treatment to be completed.

Individual electronic records of patients treated with conscious sedation with midazolam by the West Dorset Special Care Primary Care Dental Service during the first nine months were examined. Efficacy of midazolam was evaluated using patient sedation scores and operating conditions.

Planned treatment was successfully completed in 37 out of the 41 appointments (90%). Four patients were unable to have treatment carried out for reasons including cannulation refusal, suboptimal co-operation and vomiting. This study demonstrates that delivering dentist-led conscious sedation with midazolam in a primary care setting is a highly effective, cost- efficient alternative to general anaesthesia for a range of patients with anxiety and / or additional needs, and has significant potential to reduce wait times. However, the technique requires appropriately trained staff, careful patient selection together with suitable premises and equipment in line with evidence-based national policy and guidelines.

Introduction

Achieving pain and anxiety control during dental treatment is essential to deliver comfortable, patient-centred care. Dental services should offer a range of clinically appropriate, evidence- based and cost-effective management modalities1 to deliver equitable care.

The Special Care Primary Care Dental Service (PCDS) in West Dorset is commissioned to provide Special Care Dentistry (SCD) for adults and children with a range of additional, complex cognitive, physical, sensory, social and mental health needs. Many of these patients also suffer from a significant degree of dental anxiety and are unable to accept treatment with local anaesthesia and behavioural management techniques alone. Instead, they require conscious sedation (CS) or general anaesthetic (GA), particularly if the nature of dental treatment is invasive or extensive.2,3

Historically, the clinic had a conscious sedation service in which an anaesthetist (sedationist) used intravenous propofol as the sedative drug of choice for patients. A dentist carried out dental treatment with a dental nurse assisting. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, however, no anaesthetic colleagues were available as dental services returned to normal and a new conscious sedation service was required.

Conscious sedation with midazolam

Conscious sedation with midazolam delivered via oral, intranasal, intravenous routes, or used in combination, can be an effective adjunct to dental treatment for many patients with dental anxiety and / or additional needs.

The sedative, anxiolytic, amnesic effects and wide margin of safety of midazolam, together with its skeletal muscle relaxation and anticonvulsant qualities, make it a popular choice in dentistry, despite the absence of analgesic properties. Midazolam is highly lipid-soluble at physiological pH and its mechanism of action through Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediated opening of chloride channels allows a length and depth of sedation adequate for most patients to undergo routine dental procedures.4 It allows protective reflexes to be maintained and serious complications are limited, when carefully administered.5

Furthermore, conscious sedation with midazolam can be delivered locally in primary care by the same (trained) dental team already familiar to the patient.6 It offers greater flexibility and treatment may be delivered more promptly than GA in secondary care, where provision may be limited by extensive theatre waiting lists.7 It is less resource-intensive and more cost-effective for the provider, requiring a single, trained operator-sedationist and trained dental nurse.8

The lead author consulted with key local stakeholders, policies andnational guidance documents8,9 to outline the new service and address any concerns. Safety and quality were assured by following the evaluation checklist current at that time from the Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD).10 Subsequently, a business case was presented to the senior management team. Once agreed, the service provided one full day per week, allowing for two morning appointments and one afternoon. Appointment lengths were either 90 or 120 minutes. Two dentists had the required postgraduate training and up-to- date practical experience to provide the sedation. Scenario-based medical emergency training was organised for the whole team prior to launching the service.

Aim

To evaluate the new sedation service by assessing the efficacy of conscious sedation with midazolam in a special care dental primary care setting for patients aged 12 years and above; by identifying whether it provided operating conditions that were sufficient to allow dental treatment to be carried out as planned.

Method

This study retrospectively evaluated individual electronic notes of all patients treated with conscious sedation with midazolam by the West Dorset Special Care PCDS from December 2020 to September 2021. Some patients had more than one episode of treatment during this period. Since existing processes and practice were evaluated in line with local and national guidance, ethical approval was not considered necessary.

Patient journey

Patients were selected for their suitability to have sedation in aprimary care setting according to rigorous pre-operative assessment of medical history and American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) grading,11 as well as an airway assessment.12 Baseline blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation, heart rate, height, weight and body mass index were also measured as part of the physical examination. All patients were required to be escorted by at least one responsible adult who had no other caring duties that day / night. Escorts had to comply with remaining on the premises throughout the appointment and accompanying the patient safely home afterwards in a privately owned car or taxi. They were also instructed to look after the patient for the rest of the day, preferably overnight.

Written and verbal pre- and post-operative operative instructions were given to every patient and escort(s). There was also a written easy read version to provide, as appropriate, for patients with cognitive disability. Patients were instructed to have only a light meal, preferably at least two hours before their appointment. Written, informed consent was obtained for each patient and best interest decisions were made for those patients who lacked mental capacity.

Sedation was carried out in the Department of SCD at Dorset County Hospital, by an experienced Specialist in SCD and final year SCD Training Registrar (StR), assuming the roles of first and second ‘appropriate persons’. The dentist role was sedationist-operator, with the Specialist also assuming a supervisory role for the StR. A dental nurse was always present to assist, but not all were sedation qualified.

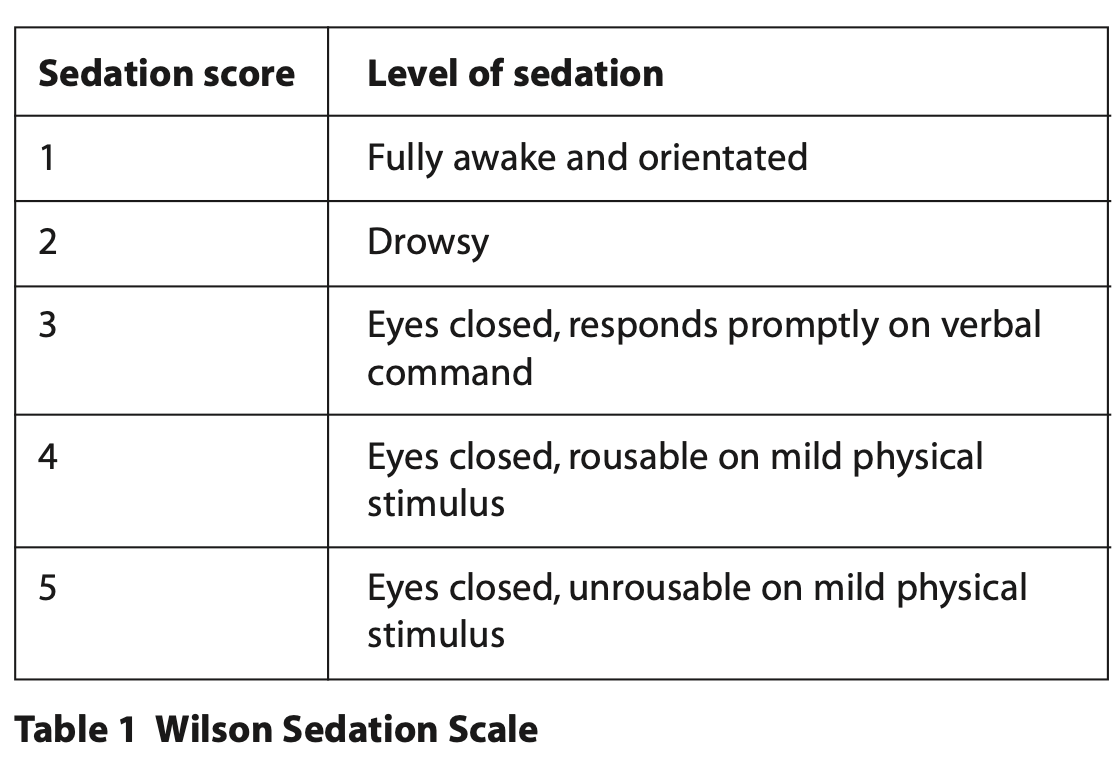

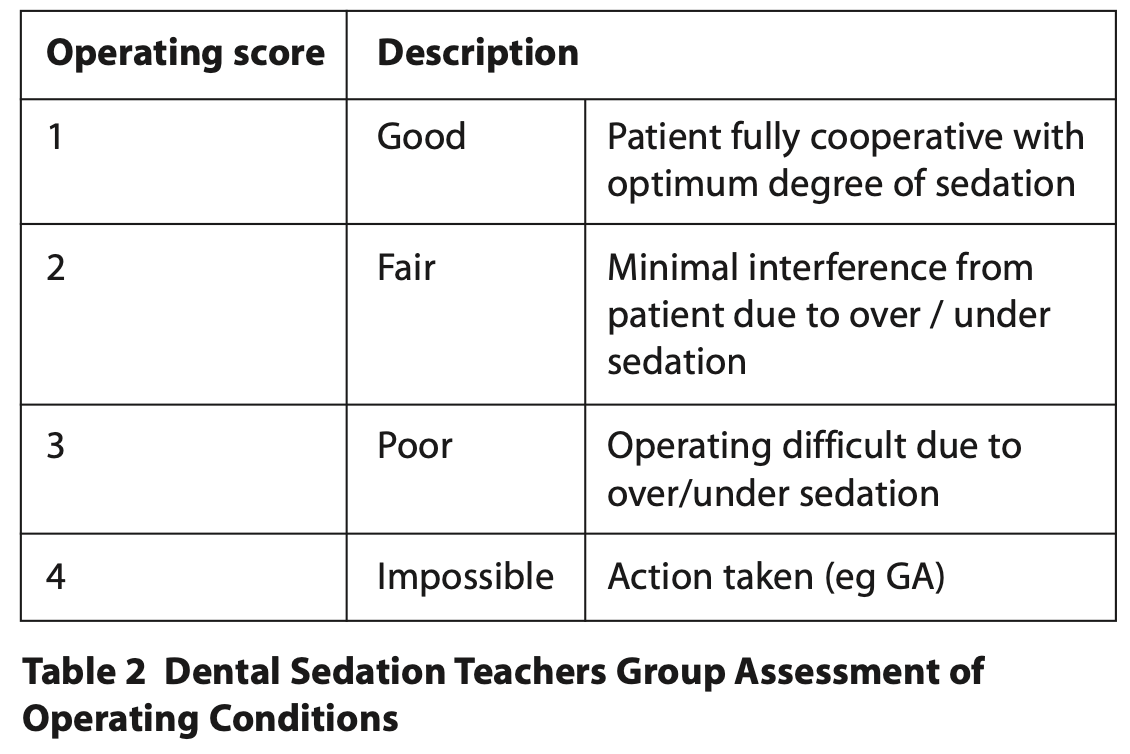

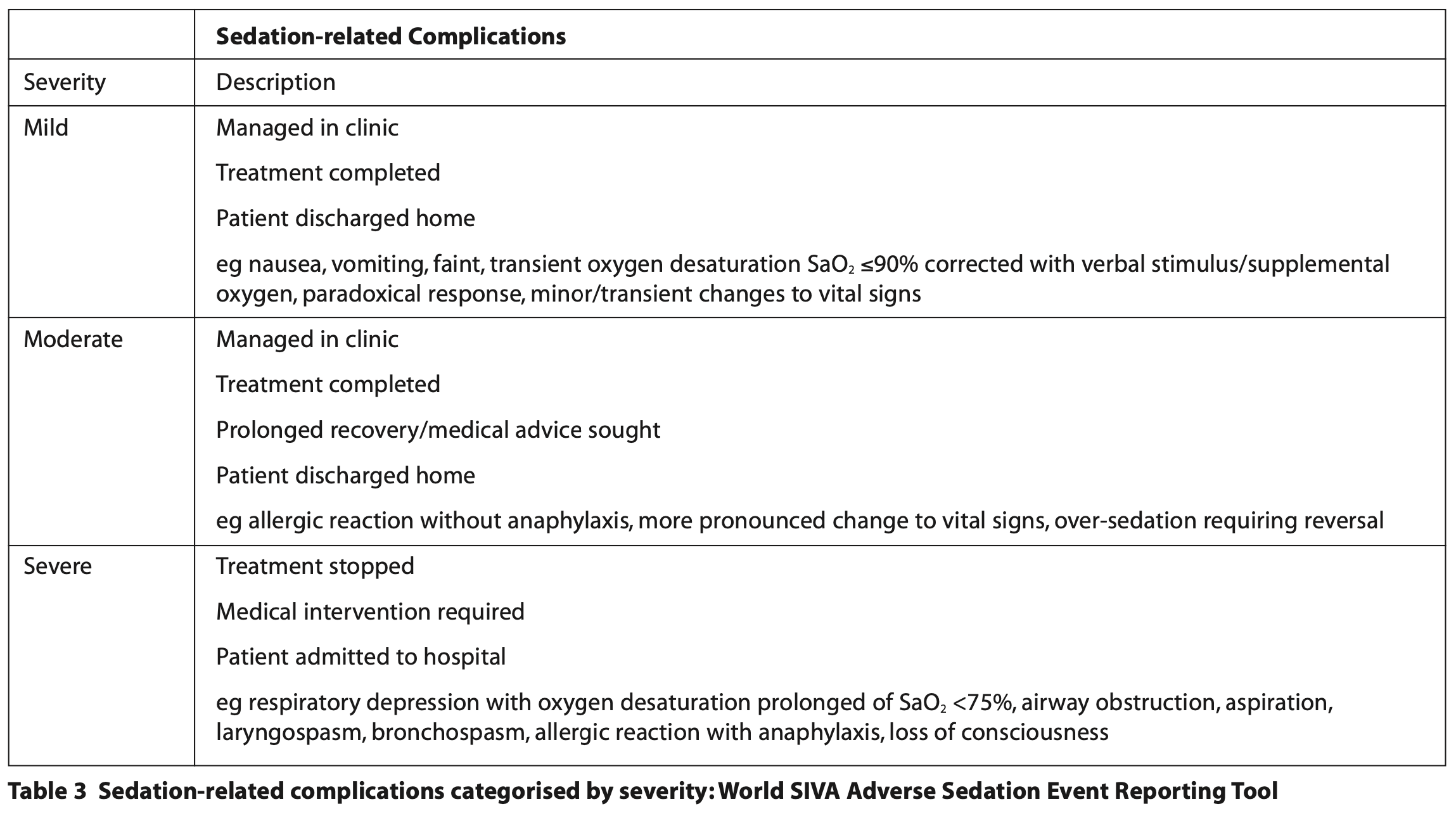

On arrival at the department, patients were checked in for their appointment following national guidance9 to ensure all was well to proceed. Despite their anxiety, most patients were able to cope with cannulation with behaviour management techniques. However, patients unable to comply with cannulation (including those exhibiting more challenging behaviours), were administered midazolam on arrival to the clinical setting as either 20 mg (2 x 10 mg/2 ml) orally in a concentrated drink or 10mg (0.25 ml of 40 mg/ml) intranasally delivered via a mucosal atomisation device. Once sufficient anxiolysis was achieved, cannulation was attempted. Midazolam (5 mg/5 ml) was titrated as per the local standard operating procedure and national guidance8 with the aim of relaxing the patient to the point of allowing dental treatment. Blood pressure, heart rate and arterial oxygen saturation were monitored and recorded throughout. Efficacy of midazolam was judged by evaluating the patient sedation scores and operating condition scores13, 14 (Tables 1 and 2) for each treatment episode and whether treatment was achieved as planned. Sedation-related complications or adverse events have been described with reference to the World SIVA Adverse Sedation Event Reporting Tool15 (Table 3). Flumazenil was available in case of complications, or prolonged recovery.16

Recovery took place in surgery with the same sedating dental team. All patients / escorts received a post-operative conscious sedation treatment summary detailing the route and dose of midazolam received, type and dose of any local anaesthetic received and a list of all dental treatment completed at the appointment. This summary was particularly important as a communication tool for patients living in supported accommodation where different staff members would be caring for the same patient and details of their sedation appointment would need to be relayed accurately. Contemporaneous notes were recorded on the Trust’s electronic notes system.

Data collection

An Excel spreadsheet was used to collect the following information about each treatment episode:

- Patient demographics: age, gender, patient status (ie core or referred in for care)

- Previous experience of dental treatment: no treatment, local anaesthetic only, inhalational sedation with nitrous oxide, oral or intranasal midazolam only, intravenous midazolam, intravenous propofol or general anaesthesia

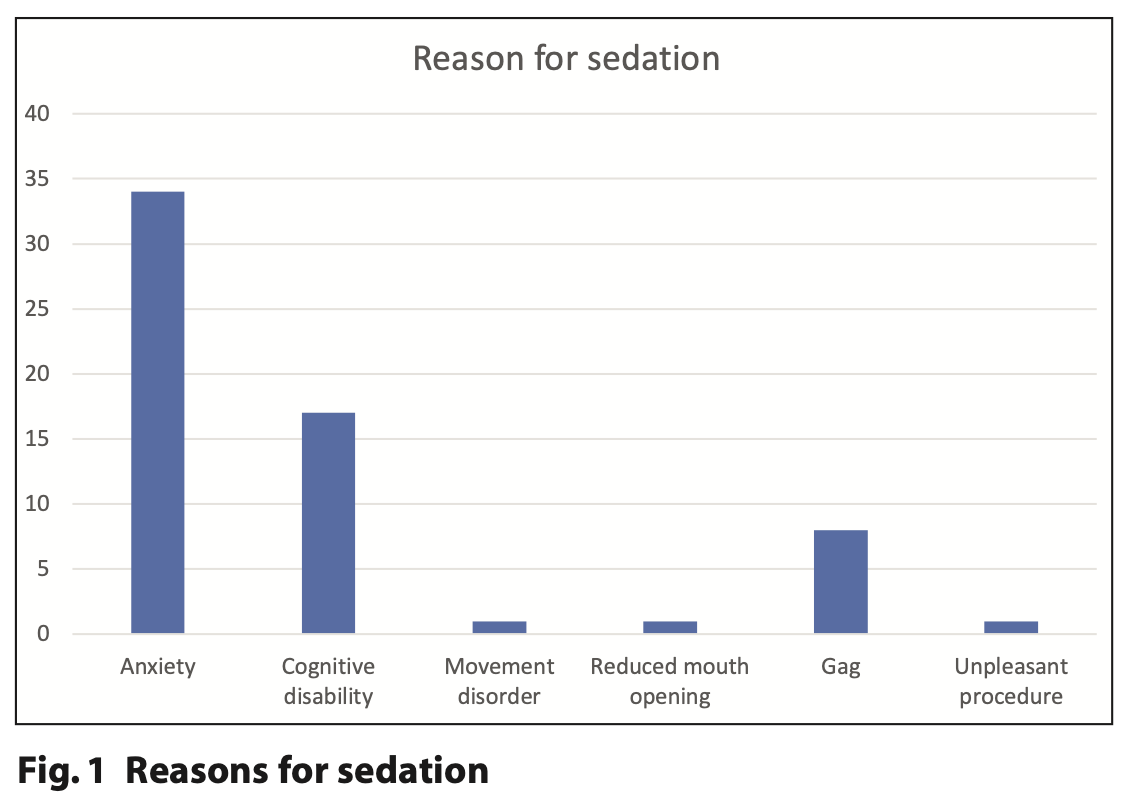

- Reason for sedation: dental anxiety, cognitive disability, movement disorder, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems causing restricted mouth opening, sensitive gag reflex or unpleasant procedure

- Intended Treatment: oral examination, dental x-rays, scaling, restorative (including root canal treatment), routine and surgical exodontia, impression-taking

- Use of oral midazolam as an adjunct

- Use of IN midazolam as an adjunct

- Dose of IV midazolam

- Sedation score

- Operating conditions

- Whether treatment was completed as planned

- Complications.

Results

The study evaluated all 41 sedation appointments from the period December 2020 to September 2021, when the sedation service was temporarily paused owing to staff sickness and maternity leave. Any sedation appointments not utilised owing to cancellation or patients failing to attend were excluded from the data.

Thirty-five patients utilised the new service during this time with a slightly higher proportion of female patients (n = 20) compared to males (n = 15). The youngest patient in the sample was 15 years old and the oldest, 87 years. Most patients were regular, core patients in the department (n = 24), whilst 11 patients had been referred from general practice for completion of specific treatment. ASA grades were either grade I (n = 12) or II (n = 23).

Nine patients had no prior sedation experience at all, and seven patients had experience of only GA. One patient had experienced both intravenous propofol and GA in the past and a minority of patients (n = 3) had been treated with local anaesthetic alone. Of those patients who had experience of sedation, most had been given propofol (n = 13), with slightly fewer having intravenous midazolam (n = 6) and only three having oral or intranasal midazolam as a standalone modality.

Reasons for sedation

Reasons for sedation are shown in Figure 1. All the patients in the sample had moderate to severe dental anxiety (MDAS scores 19 to 25), including needle phobia, and had identified at least one or more additional need. In this study, the most common additional need was cognitive disability including learning disability, autism and dementia (n = 17). This was followed by those with a profound gag reflex (n = 8), movement disorders (n = 1) and reduced mouth opening owing to temporomandibular joint dysfunction (n = 1). One of the patients would usually have local anaesthetic for fillings but opted for sedation because they were having two episodes of multiple dental extractions.

Sedation routes and dose

Only six patients required a pre-treatment dose of either oral or transmucosal midazolam to facilitate cannulation, and no pre- appointment benzodiazepine was prescribed for any patients for their car journey. Thirty-nine episodes of intravenous sedation were carried out over the period. Midazolam dosage ranged from 1 mg to 14 mg, with a mean dose of 6.6 mg. A sedation score of 3 was achieved in 17 of the sedation episodes and 22 achieved a score of 2.

Treatment outcomes and complications

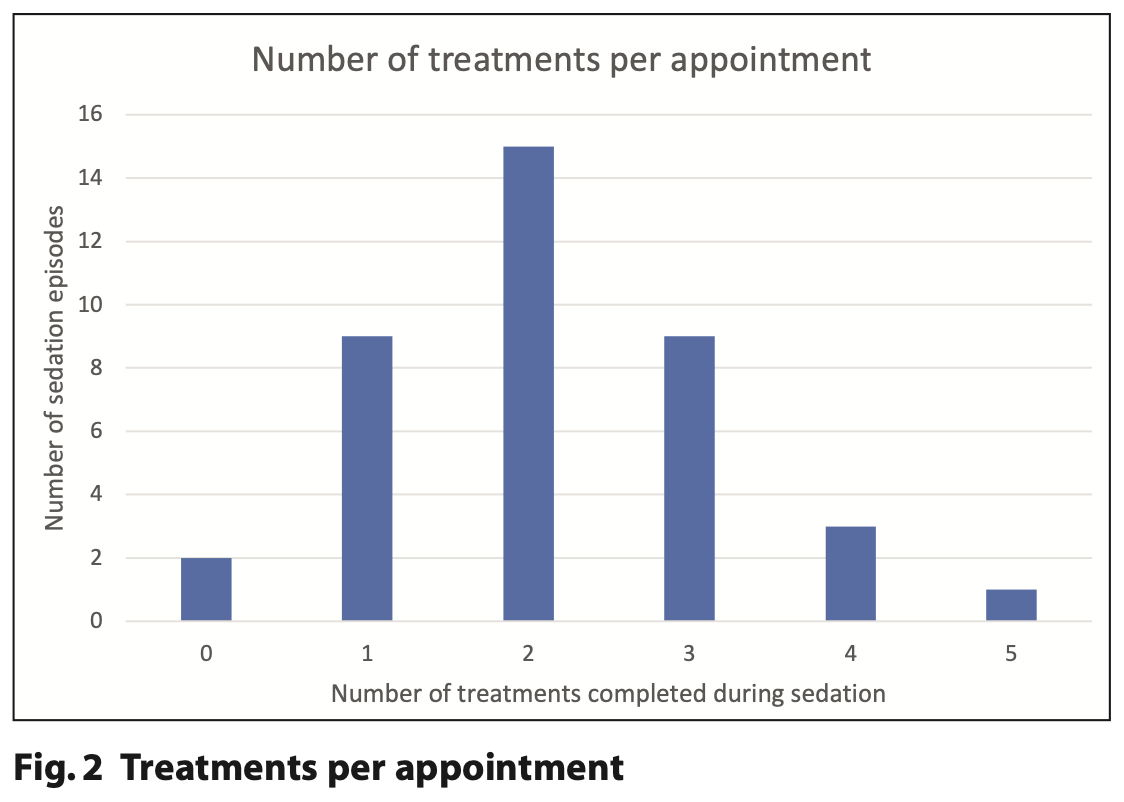

Of the 39 sedation episodes, operating conditions were either 1 (n = 22), 2 (n = 15), 3 (n = 1) or 4 (n = 1). Treatment was successfully completed as planned in 37 out of the 41 appointments (90%), which included oral examination, intra-oral radiographs, prophylaxis, restorative dentistry, exodontia and impression taking. Most patients had combinations of these treatments as shown in Figure 2.

Four of the patients were not able to have treatment carried out as planned. Two patients refused cannulation, so treatment was abandoned, despite one of these having received pre-treatment oral midazolam in the clinic. The other patient’s extreme anxiety meant that they were unconvinced that sedation would work, so refused the pre-treatment oral or intranasal midazolam.

Two of the four unsuccessfully treated patients did have sedation, but it was insufficient for treatment to be carried out safely; one achieved a maximum sedation score of 2, appeared suitably relaxed and coped well with oral examination, but became agitated on attempts at operative dentistry to the extent that it was not possible to give local anaesthetic or use handpieces (operating condition score 3) so treatment was abandoned.

As per the World SIVA Adverse Sedation Event Reporting Tool the other patient, who had a learning disability and a profound gag reflex, had a mild sedation-related complication as they vomited during radiograph taking, which meant that treatment was abandoned thereafter. These patients recovered uneventfully and subsequently had treatment completed with a further IV midazolam appointment (n = 2) or GA (n = 2) as alternatives. In recovery, five patients experienced moderate sedation-related complications. One experienced delayed recovery and four remained unsteady on their feet and posed a falling risk. They each required reversal of sedation by administration of flumazenil in a single, bolus dose of 500 micrograms after 60 minutes from the last midazolam titration.

Discussion

Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruption to healthcare provision, it also provided opportunities to rethink the status quo. The loss of the original sedation service in the Special Care PCDS in West Dorset left many patients waiting for treatment without a definite resolution, a fact that was recognised on the Trust’s risk register. By utilising existing clinical space, resources and skills within the PCDS team, the new sedation service provided prompt patient access to this type of care. The two sedating dentists had postgraduate sedation qualifications and considerable experience sedating special care patients, but no dental nurses from that site were sedation trained. However, there was an established dentist-led conscious sedation service elsewhere in the Trust, where a significant proportion of dental nurses were sedation qualified. Having their support was key to the success of the service and helped translate the planning of the new service into action. Some dental nurses had expressed ambivalence about a dentist-led midazolam sedation service but, together with clear communication, the benefits of multisite team working were soon realised, helping to improve team relations and clinical supervision. In turn, this has provided an opportunity for other West Dorset dentists and dental nurses to pursue career development in sedation, with a dentist and a dental nurse (so far) having since successfully completed qualifications.

A further benefit to the service is the relatively cost-efficient nature of a dentist-led midazolam sedation service compared with anaesthetist-led or general anaesthetic pathways.17 Clinical effectiveness for both patient and provider is also key.18 Use of scoring systems to measure the operating conditions and level of sedation offers quantitative evidence that describes whether conscious sedation with midazolam permits dental treatment to be undertaken as desired. Of the many sedation scoring systems available,19 the Wilson sedation scale13 for level of sedation and the Dental Sedation Teachers Group (DSTG) operating conditions14 scoring systems were chosen for their ease of use, consistency and familiarity in that they are already used across the Trust. Both scores are documented for each sedation episode, offering a snapshot of efficacy at that time.

Patients were able to be seen without further delay and access to dental treatment improved immediately for those patients unable to have treatment with less invasive techniques. Since midazolam has a wide margin of safety and could be repeated over several appointments, more restorative work and less exodontia was possible compared to GA.20 Verbal feedback was positive from both patients and carers with most choosing to repeat the experience for future dental care. They appreciated the much shorter waiting times for treatment, and a more flexible pathway with familiar staff and environment. The oral and intranasal adjuncts for those resistant to cannulation, which had not been routinely offered previously (by anaesthetists using propofol), removed yet another barrier to dental care. Not having to fast / starve pre-operatively was more acceptable and the halogenated gases widely used in GA also have a long-term impact on global warming which should not be overlooked.21

Conclusions

Adding dentist-led conscious sedation to the range of treatment modalities offered in West Dorset significantly expedited treatment for patients on a waiting list which had been extended by the restrictions placed by the COVID-19 pandemic and has since reduced wait times by facilitating treatment for new patients within weeks.

Success with midazolam requires careful patient selection, a suitable environment and compliance with national policy and guidelines, together with regular audit and reflection.22 Given these prerequisites, this evaluation clearly evidenced that midazolam, administered in a primary special dental care setting by an appropriately trained, dentist-led team, is an effective treatment modality for many patients with anxiety and / or additional needs. The West Dorset service was implemented rapidly and efficiently using existing expertise from within the PCDS. Bringing sedation ‘in-house’ for patients for whom use of midazolam is appropriate, has enabled agile planning and swift delivery of treatment, allowing multiple procedures to be carried out per appointment in a timely fashion. This has helped the service to maintain its targets to date, and puts it in good shape to continue to do so in the future.

References

1. Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD). Guidance for Commissioning NHS England Dental Conscious Sedation Services. A Framework Tool. 2013. Online information available at http://saad.org.uk/Documents/SAAD_Guidance_Commissioning_Sedation.pdf (accessed June 2023).

2. Coulthard P, Bridgman C, Gough L, Longman L, Pretty I A, Jenner T. Estimating the need for dental sedation. 1. The Indicator of Sedation Need (IOSN) − a novel assessment tool. Br Dent J 2011; 211: E10.

3. Newton T. Commentary and summary of estimating the need for dental sedation. 1. The Indicator of Sedation Need (IOSN) – a novel assessment tool. Br Dent J 2011; 211: 218-9.

4. Kapur A, Kapur V. Conscious sedation in dentistry. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018; 8: 320-323.

5. Craig D, Boyle C. Practical Conscious Sedation. 2nd Edn. London: Quintessence Publishing, 2017.

6. Binnie R, Robb N, Manton S, Bonsor S. The establishment of an intravenous conscious sedation service for adult patients in a primary dental care setting. Dent Update 2020; 47: 22–36.

7. Patel J. The advantages and disadvantages of providing minor oral surgery in primary care. RCSEng Faculty Dental Journal; 2013; 4:2 94-98.

8. Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in Provision of Dental Care. 2020. Online information available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/fds/publications/standards-for conscious-sedation-and-accreditation/dentalsedation-report-v11-2020.pdf (accessed March 2021).

9. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP). Conscious Sedation in Dentistry: Dental Clinical Guidance, 3rd ed. 2017.

10. Society for the Advancement of Anaesthesia in Dentistry (SAAD). A quality assurance Programme for implementing national standards in conscious sedation for dentistry in the UK. 2019. Online information available at https://saad.org.uk/images/Linked-Safe-Practice-Scheme-Website-L.pdf (accessed September 2020).

11. American Society of Anaesthesiologists. Physical status classification system. 2023. Online information available at https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system (accessed June 2023).

12. Hasara R. Conscious sedation in dentistry: selecting the right patient. Dental Update 2020; 47: 353-359.

13. Némethy M, Paroli L, Williams-Russo P G, Blanck T. Assessing Sedation with Regional Anesthesia: Inter-Rater Agreement on a Modified Wilson Sedation Scale. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2002; 94:3 723-728.

14. Dental Sedation Teachers’ Group. Logbook of clinical experience in conscious sedation. Online information available at https://www.dstg.co.uk/index.php/documents/document (accessed May 2019).

15. Mason, K P, Green, S M and Piacevoli, Q. 2012. Adverse event reporting tool to standardize the reporting and tracking of adverse events during procedural sedation: a consensus document from the World SIVA International Sedation Task Force. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2012; 108: 13-20.

16. Harrhy C, Robb N. The use of flumazenil in a community dental service – a service evaluation. SAAD Digest 2019; 35: 28-32.

17. McGeown D, Stapleton S, Nunn J. A cost analysis estimation of a single episode of comprehensive dental treatment under general anaesthesia for adults with disabilities. Br Dent J 2018; 224:6 442-446.

18. Wilson K, Amin K, Girdler N. Evaluation of clinical effectiveness in the provision of intravenous midazolam sedation for anxious dental patients. RCSeng Faculty Dental Journal 2017; 8: 144-149.

19. Newton T, Pop I, Duvall E. Sedation scales and measures-a literature review. SAAD digest 2013; 29: 88-99.

20. Davies D H J. A review of the use of intranasally administered midazolam in adults and its application in dentistry. Journal of Disability and Oral Health 2015; 16: 68-78.

21. Saliakelli D, Harley K. The effect of anaesthetic gases on global warming. RCSeng Faculty Dental Journal 2020; 11: 134-137.

22. NHS England. Clinical guide for dental anxiety management. 2023. Online information available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/clinical-guide-for-dental-anxiety-management/#3-conscious-sedation (accessed April 2023).