Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Patient experiences and outcomes following intravenous sedation in an oral surgery setting

A.K. Lamba*1 BDS

A. Heewa2 BDS

O. Johnson King3 BDS (Hons), BSc (Hons), MFDS RCS (Edin), MClinDent, MOrth RCS (Eng)

M. Eghtessad4 BDS, LDS RCS, MSc Oral Surgery Specialist in Oral Surgery

1At time of writing: Clinical Fellow in Paediatric Dentistry, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR. Currently: Specialty Doctor in Paediatric Dentistry, St. Thomas’ Hospital Children’s Dental Centre, Ground Floor, South Wing, St. Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London, SE1 7EH

2At time of writing: Dental Core Trainee, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR. Currently: Clinical fellow in Paediatric Dentistry, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

3Post-CCST in Orthodontics, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

4Specialist in Oral Surgery, Royal National ENT and Eastman Dental Hospital, 47-49 Huntley Street, London, WC1E 6DG

*Correspondence to: Asees Kaur Lamba

Email: Asees.Lamba@nhs.net

Lamba A K, Heewa A, Johnson King O, Eghtessad M. Patient experiences and outcomes following intravenous sedation in an oral surgery setting. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 19-22

Abstract

Intravenous sedation is a widely used method of providing elective dental treatment to patients that may be anxious, have a gag reflex or who are undergoing a difficult surgical procedure when local or general anaesthetic on its own is contraindicated.

A telephone questionnaire was conducted post extraction for those who had undergone treatment under intravenous sedation at the Royal National ENT and Eastman Dental Hospital in 2017 and 2021. We aimed to evaluate the service and demonstrate patient reported experiences and outcomes of intravenous sedation as a method for oral surgical procedures.

Results were positive, with 100% of patients opting to use this method again for dental treatment and 100% of patients recommending this method to friends and family if they were to undergo a similar procedure.

Background

Intravenous (IV) sedation is a widely used method of providing elective dental treatment to patients that may be anxious, have a gag reflex, or who are undergoing a difficult surgical procedure where local or general anaesthetic are contraindicated.1

Intravenous sedation allows for conscious sedation with patients having the ability to maintain their own airway and can be delivered by trained dentists in a primary, secondary or tertiary care setting without an anaesthetist present.2

In the UK, the most common method of IV sedation involves single drug sedation with intravenous midazolam via a titrated dose, especially due to its rapid onset and anterograde amnesia, leading to anxiolysis.1 It is effective in patients with moderate or severe anxiety, planning unpleasant surgical procedures and as an alternative to general anaesthetic.2 The drawbacks of midazolam include respiratory depression, disinhibition, a requirement of supervision for eight hours post-operatively and no analgesic properties. Midazolam must not be used in patients with a benzodiazepine allergy and should be used with caution in pregnant / breastfeeding patients, patients with severe psychiatric disorders, patients with hepatic / renal impairment, those who actively use substances and / or drugs and those who are needle phobic. To administer midazolam, clinicians must have relevant training as per standards laid out by the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry (IASCD) and NHS England in 2015, and pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative monitoring must be performed.3,4,5

Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMS) assess the quality of care delivered from the patient's perspective, whereas Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMS) are tools to capture a person’s perception of their experience with healthcare or a service.6

Aims

We aimed to retrospectively evaluate the service and assess patient satisfaction prior to sedation, during sedation and after sedation when undergoing dentoalveolar surgery in the Oral Surgery Department at Eastman Dental Hospital, to ensure the service provided was in accordance with the 2015 IASCD (Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry) guidelines.3

Methods

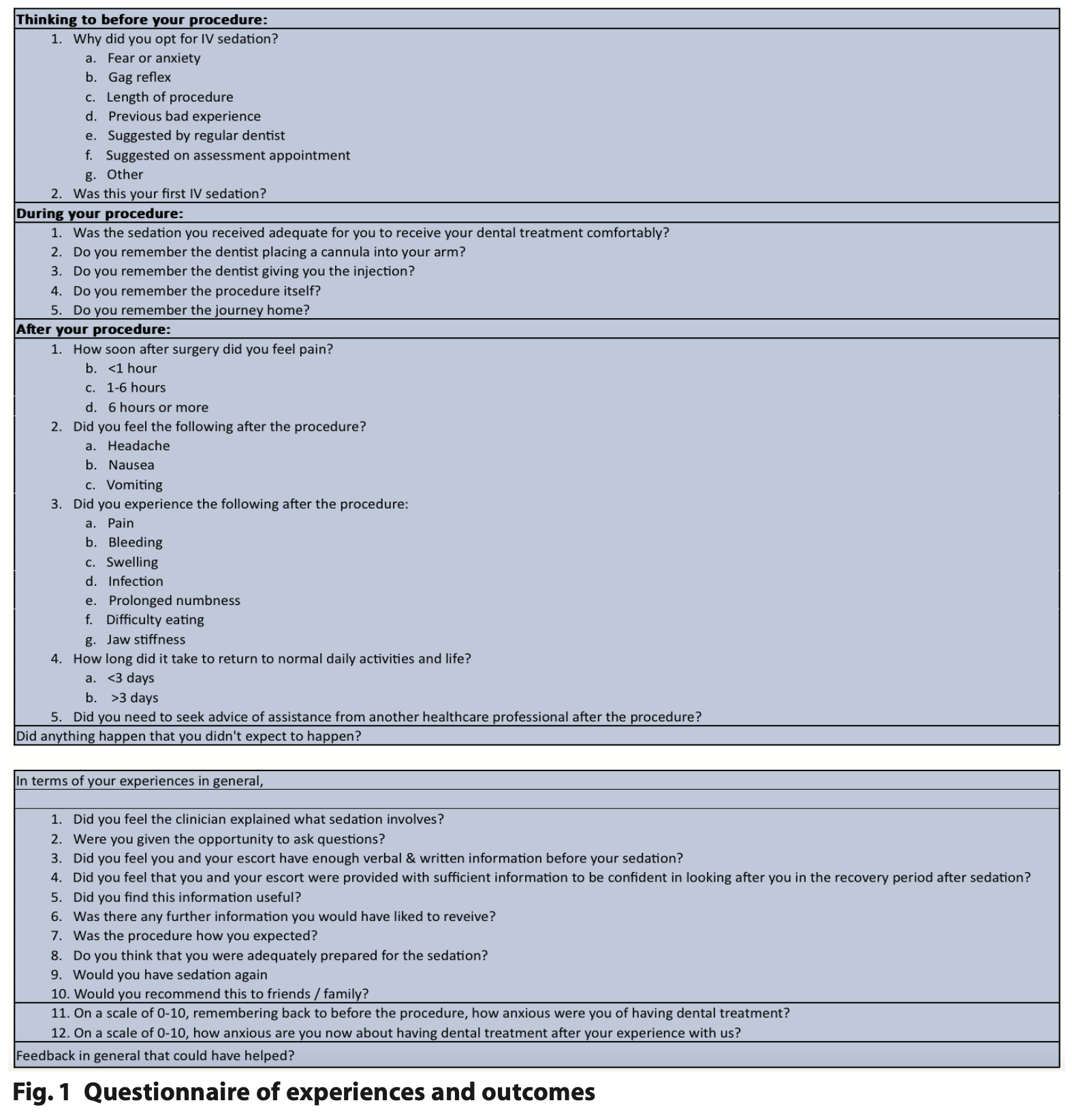

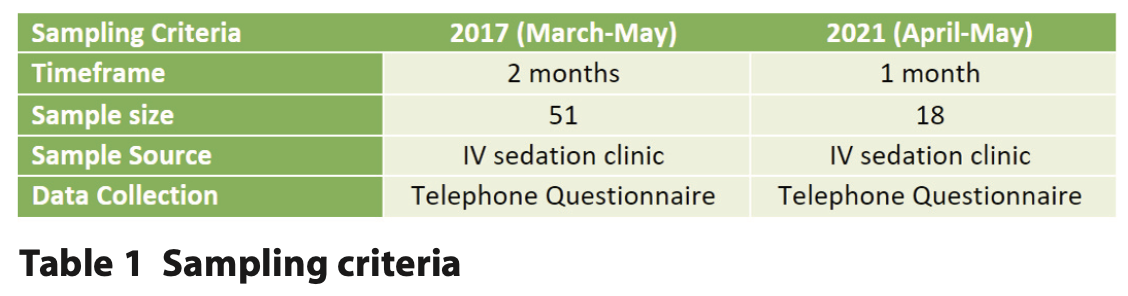

A single retrospective questionnaire was conducted via telephone interview one to two weeks post intravenous sedation for dental extractions, exploring patient reported experiences and outcomes for the three phases of treatment: pre-operative, peri-operative and post-operative (Figures 1 and 2). The patients consented to participate prior to their sedation treatment and our selection criteria, demonstrated in Table 1, included any patient over 18 years of age undergoing an oral surgical procedure under intravenous sedation in the Oral Surgery Department at the Royal National ENT and Eastman Dental Hospital. Two cycles were conducted: the first in 2017 and the second during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. There was a reduced sample in the latter cycle due to reduced activity in the department as per the Trust’s guidance. A total of 51 patients responded for the initial cycle in 2017 and 18 for the second cycle in 2021. Outcomes such as pain and infection can occur up to a week post procedure, therefore patients were called after one week to minimise symptom-based bias during the recovery period. A period of one week was given to attempt to contact the patient.

The questionnaire was adapted and tailored for intravenous sedation using the NHS commissioning guidance.4,5 The questionnaire included simple ‘yes / no’ questions and short answer feedback questions, separating their experiences at the department including the day of treatment and surgical and sedation outcomes. Individual feedback was given to the clinicians mentioned in this survey and the results were presented at a local departmental audit meeting.

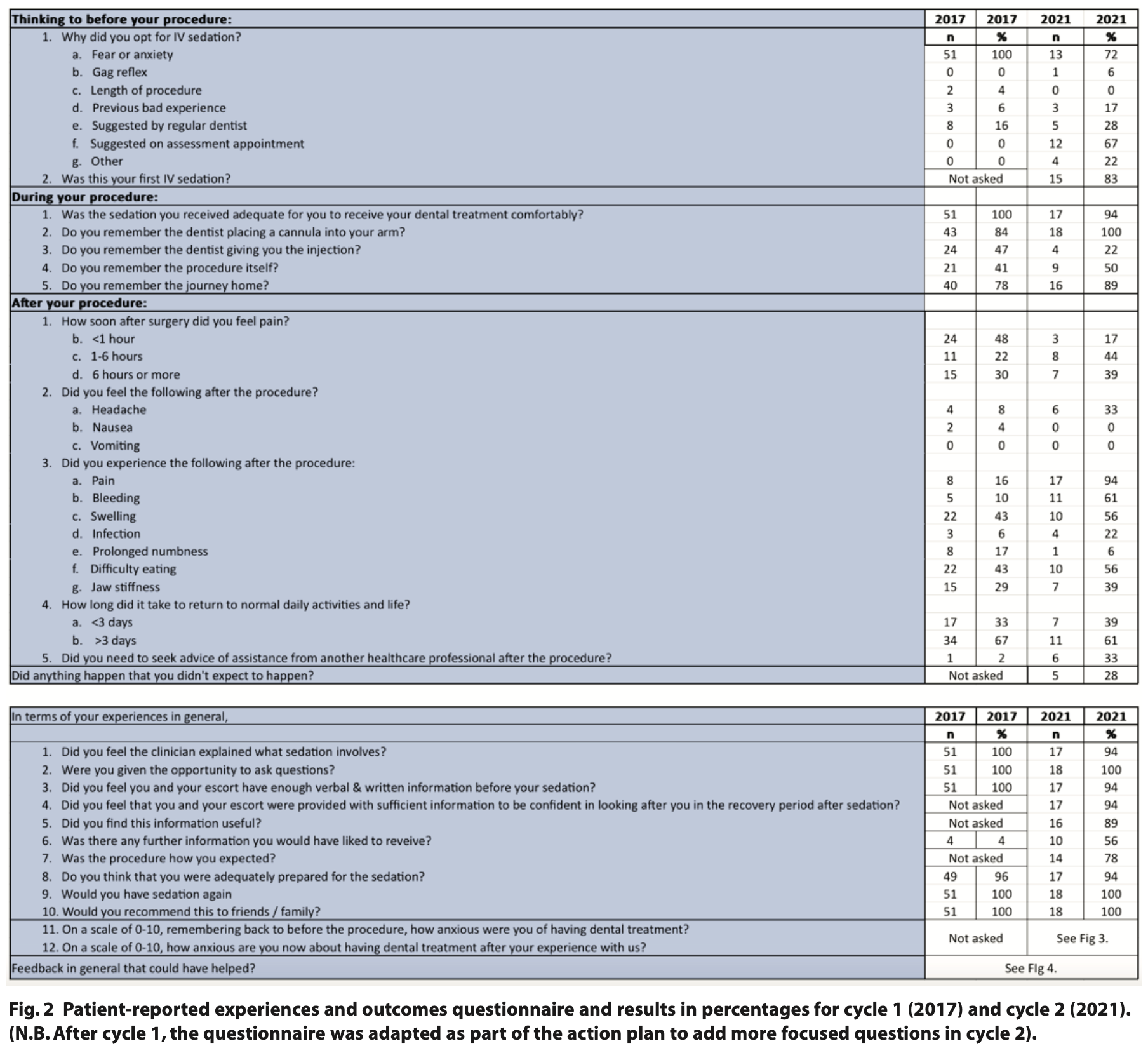

Results

A total of 51 patients over a two-month period responded for the initial cycle in 2017 and 18 for the second cycle in 2021, the results of which are outlined in Figure 2 (on page 21). The second cycle was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic where departmental activity was reduced, leading to a reduced patient sample. As demonstrated in the results table, the questionnaire was also adapted with more focused questions on patients’ experiences and outcomes in the second cycle.

Patient reported experience measures (PREMS)

Cycle one in 2017 demonstrated a good patient experience, with 100% of patients reporting satisfaction with the service in all categories apart from 4% of patients reporting they wanted more information and therefore weren’t adequately prepared (Figure 2 on page 21). Our action plan included presentation locally to the department and re-auditing this.

Cycle two in 2021, mid-COVID-19 pandemic, yielded reduced satisfaction with 100% patients reporting satisfaction with the service in three of ten questions (Figure 2 on page 21). The majority of patients (56%) felt they required further information prior to their procedure. However, it is important to recognise that the results were more varied given the smaller patient sample, leading to greater differences in percentage. At the height of the pandemic, more complex procedures were carried out with intravenous sedation due to cancelled general anaesthetic lists, therefore difficult extraction or complex procedure experiences are likely to have contributed to this. Of note, in both cycles, was the finding that 100% of patients would opt to have sedation again and 100% would recommend sedation to friends and family (Figure 3).

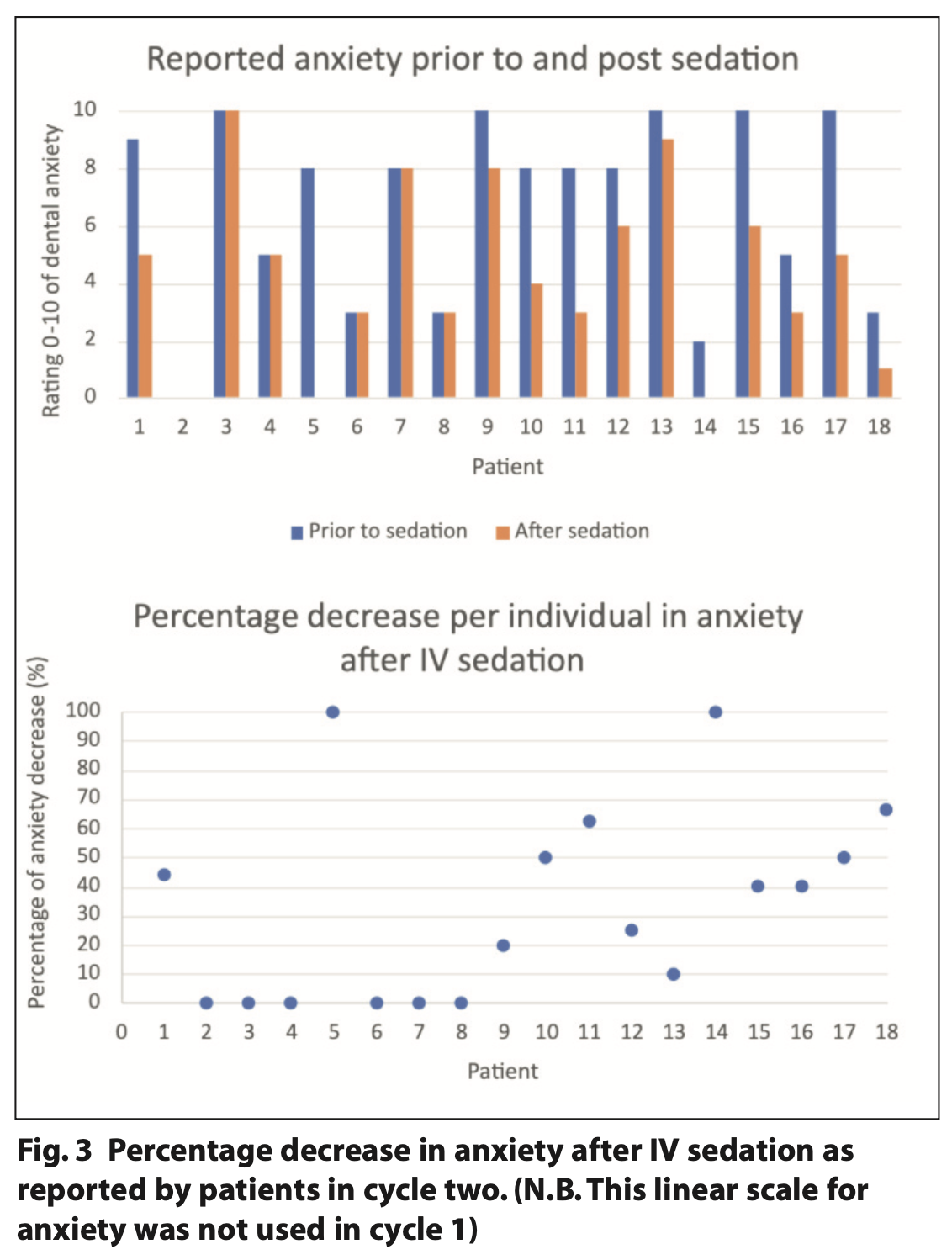

In the second cycle, anxiety levels were also reviewed, with 67% of patients reporting up to 100% reduction, and 33% of patients reporting no reduction in anxiety levels, demonstrating the varied effect of anxiolytic properties of IV midazolam (Figure 2) and no clear reduction in anxiety to dental treatment for all patients.

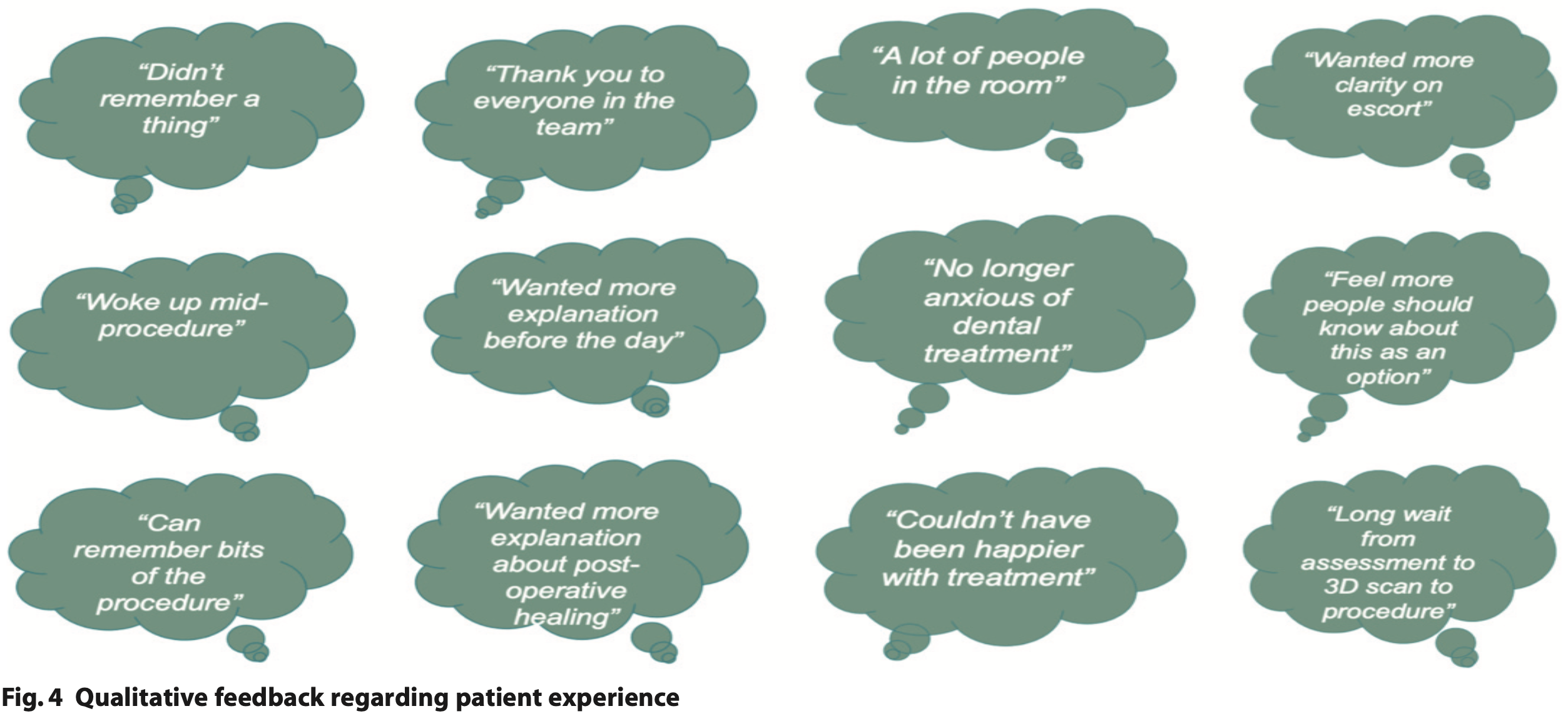

Qualitative data were collected on patient experiences, whether patients felt the events did not go as they had expected, and patients were given an opportunity to provide feedback to the department. Quotes from the qualitative data can be found in Figure 4 and full responses were directly discussed with the department to ensure service improvement.

Patient reported outcome measures (PROMS):

Cycle one in 2017 demonstrated all patients opted for IV sedation due to fear and/or anxiety and some due to suggestion from their local dentist (Figure 2). 60% of patients did not remember the injection or procedure. Postoperatively, nearly one in two patients felt pain within an hour of the procedure, leading to a discussion about pain management with clinicians at our local departmental meeting as part of the action plan. In cycle two in 2018 the reasons for opting for IV sedation were more varied (Figure 2).

In cycle two 67% of patients had IV sedation options discussed as part of their assessment appointment. 20% of patients did not remember the injection, however, 50% remembered the procedure, which could have been due to lengthy procedures or inadequate sedation administered. The majority of patients experienced pain post procedure within one to six hours or more than six hours after the procedure as expected once local anaesthetic wore off.

From cycle one to cycle two, 50% more patients reported post- operative bleeding, however, with the limitation of ‘yes / no’ questions, there was no specification on whether this was minimal post-operative bleeding as expected after an extraction; bleeding which required pressure with gauze to stop, or bleeding which required attendance to a local dentist or Emergency Department to stop. Similarly, more patients reported pain post procedure, which could be attributed to the department undertaking more complex procedures during the pandemic under IV sedation, however, without further data analysis on procedural complexity this cannot be confirmed.

Of note was the finding that the time taken to return to regular daily activities remained similar for cycles one and two, potentially demonstrating the similar recovery period for different oral surgical procedures.

Action plan

Cycle one was presented at a local departmental meeting and led to a discussion about pain management with clinicians, to ensure adequate advice was given to patients based on the procedure.

From cycle one to cycle two, the questionnaire had been adjusted to include ‘yes / no’ questions such as asking: if it was the first time they experienced IV sedation; if they felt they and their escort were provided with sufficient information prior to the appointment and whether the information given was useful. Open ended questions were added to ask whether the patient felt the events did not go as expected and a linear scale of zero to ten was used to record patients’ perceived dental anxiety prior to their procedure and afterwards.

The action plan after cycle two of the PREMS and PROMS included: local presentation to the department within a month of data collection; adjustment of the sedation and procedural leaflets to reflect tailored post-operative management within a month of findings; consideration of patient feedback; and re-audit once normal activity resumed after the COVID-19 pandemic, at the latest by 2023.

Discussion

With the small sample sizes, we cannot provide any statistical analysis, however, we can see a maintenance of 100% satisfaction of patients with the service provided at Eastman Dental Hospital (Figure 2). We can determine that IV sedation in oral surgery is a valuable tool, with 100% of patients opting to recommend or use intravenous sedation again for a repeat procedure.

There has been a slight, but seemingly insignificant, decrease in outcomes, with nearly 50% of patients remembering parts of the procedure (Figure 2). This could be due to the level of sedation they were kept at, which is ultimately dependent on the operator, the length of procedure and patient factors. Situational factors including change of staff, hospital and operating during the COVID-19 pandemic have all impacted our service during the re- audit period, including opting for sedation over general anaesthetic for complex procedures to reduce waiting time. However, there was a measurable decrease of anxiety in some patients as can be seen in Figure 3, demonstrating how IV sedation can provide anxiolysis with its anterograde amnesia properties.

The sample size has limited the conclusions we could draw from the data; however, it indicates we are still maintaining a high standard of care, with some areas of improvement required around pre and postoperative information, especially with regards to the procedure.

To improve the service, improvements in qualitative data collection should be made to include collecting specific data on from where patients sought help if required, which would highlight points of access to care including their local dentist, general practitioner and Emergency Department. Furthermore, the service could then be further improved by outlining the most effective pathways for care and follow up via the operating clinician.

Intravenous sedation remains an effective method with a wide safety margin for treating patients who require oral surgical procedures, without the need for general anaesthetic. This means aspects such as waiting times and times taken in the hospital can be reduced, thereby increasing the efficiency provided in a department.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Eastman Dental Hospital Oral Surgery department for approving and registering this project.

Declarations of Interest

No declarations of interest.

Ethics

Ethics approval was not required.

References

1. Yoon J Y, Kim E J. Current trends in intravenous sedative drugs for dental procedures. J Dent Anesth Pain Med 2016; 89-94.

2. Craig D C, Skelly A M. Practical Conscious Sedation. 1st ed. London: Quintessence, 2004.

3. Sedation Analgesia and Anxiety Management for Dentistry. Standards for Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care – Report of the Intercollegiate Advisory Committee for Sedation in Dentistry. 2015. Online information available at https://www.saad.org.uk/images/Linked-IACSD-2015.pdf (accessed 31.07.2023).

4. National Health Service England. NHS England Guide to Commissioning in Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine Specialties. 2015. Online information available at: https://www.dental-referrals.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/guid-comms-oral.pdf (accessed 31.07.2023).

5. National Health Service England. NHS England Guide to Commissioning Specialist Dentistry Services. 2015. Online information available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/intro-guide-comms-dent-specl.pdf (accessed 05.05.21).

6. Grossman S, Dungarwalla M and Bailey E. Patient-reported experience and outcome measures in oral surgery: a dental hospital experience. Br Dent J. 2020; 70-74.