Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

The use of inhalation sedation to manage delayed eruption of permanent teeth, hypodontia and caries in a child patient

A. Heewa*1 BDS, MFDS RCS (Edin.)

A.K. Lamba2 BDS

H. Syed3 BDS, MJDF RCS (Eng.), MPaeds RCS (Edin.)

R. Kaur4 BDS, MFDS RCS (Eng.), MSc Paed Dent, FDS RCS (Eng.)

R. Whatling5 BSc, BDS, FDS RCS (Eng.) (Paed Dent), MPaed Dent RCS (Eng.), MClinDent (Paed Dent), MFDS RCS (Eng.)

1 Dental Core Trainee, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

2 Clinical Fellow in Paediatric Dentistry, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

3 Specialist in Paediatric Dentistry, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

4,5 Consultant in Paediatric Dentistry, Royal London Dental Hospital, Turner Street, London, E1 1FR

*Correspondence to: Allaan Heewa

Email: Allaan.Heewa@nhs.net

Heewa A, Lamba A.K, Syed H, Kaur R, Whatling R. The use of Inhalation Sedation to manage delayed eruption of permanent teeth, hypodontia and caries in a child patient. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 50-53

Case Summary

A ten-year-old medically healthy male, was referred to The Royal London Hospital’s Paediatric Dental Department due to delayed eruption of upper central incisors. Clinical and radiographic examination confirmed the diagnosis of carious first permanent molars, hypodontia of the LR5 and delayed eruption of multiple permanent teeth.

Following attendance at a joint orthodontic paediatric clinic, three first permanent molars (UR6, UL6 and LL6) were extracted, whilst the remaining lower right first permanent molar (LR6) was fissure sealed. Soft tissue exposure was advised and performed on seven unerupted permanent teeth (UR1, UL1, UL3, UL4, UL5, LL4 and LL5). Successful treatment appointments have been achieved with inhalation sedation. Inhalation sedation as an adjunct to chairside treatment under local anaesthetic has allowed treatment to be completed, without the need for general anaesthetic.

Patient details

Gender: Male

Age at start of treatment: 10 years 5 months

Pre-treatment assessment

History of presenting patient’s complaints

The child presented in 2018 to the new patient assessment clinic following a referral from their general dental practitioner (GDP) regarding their unerupted upper central incisors (UR1, UL1). The aesthetic impact had caused low self-esteem and reluctance to smile, affecting his quality of life in important, developmental years.

Relevant medical history

Medically healthy, no medications and no known drug allergies.

Dental history

High caries risk as a regular attender and previous dental extractions under general anaesthetic due to caries at five years of age. He reported unsupervised brushing twice daily, with a manual toothbrush and fluoridated toothpaste, along with a high cariogenic diet. Notably, there was a family history of unerupted teeth (impacted canines) and hypodontia from the maternal side.

Clinical examination

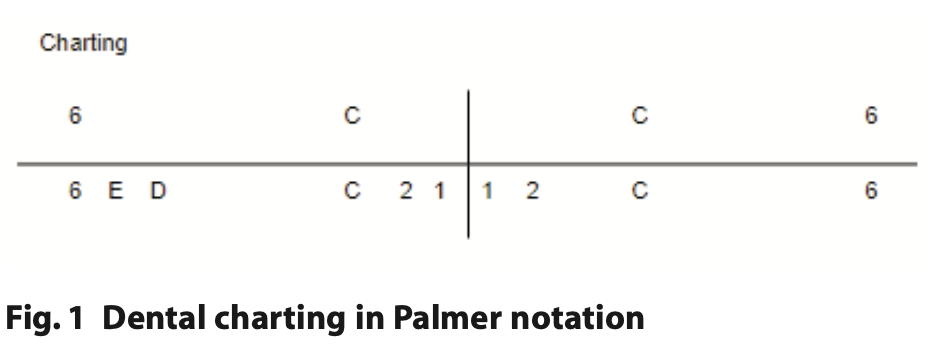

On examination (06.01.2018), extraoral findings were unremarkable. Intraorally, soft tissue examination showed inflamed gingivae and poor oral hygiene. Basic periodontal examination (BPE – British Society of Periodontology) revealed scores of 1 in all sextants. Full dental charting with Palmer notation was completed as can be seen in Figure 1.

General radiographic examination

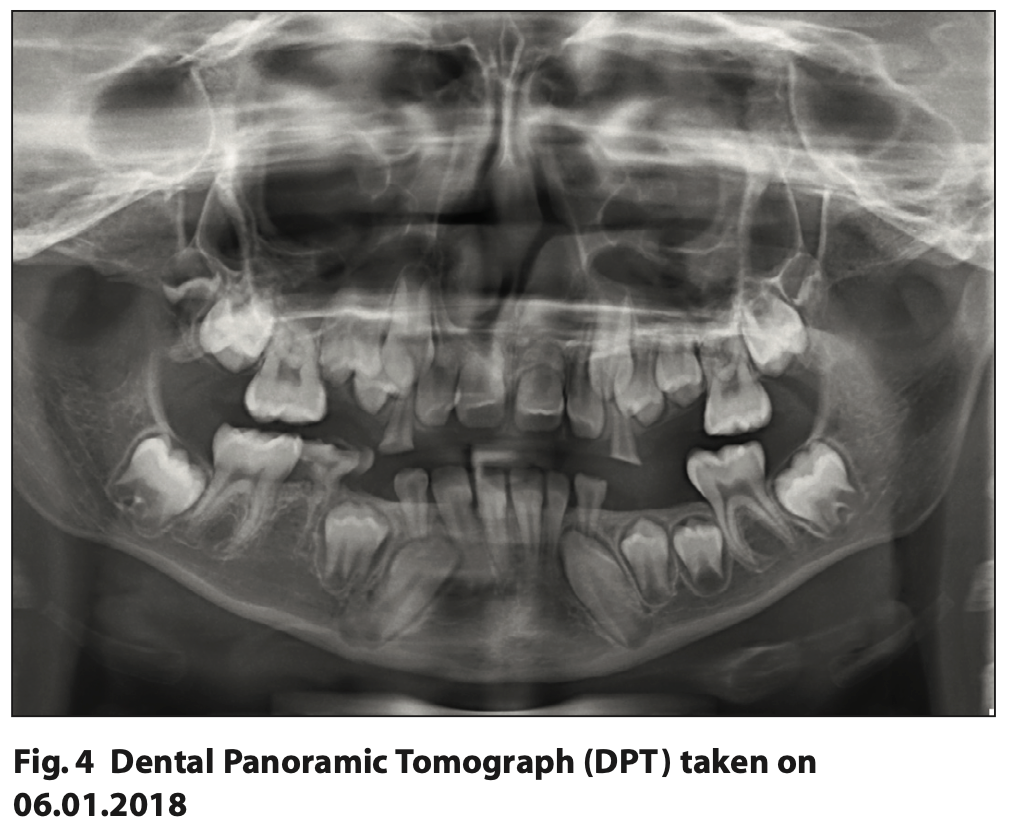

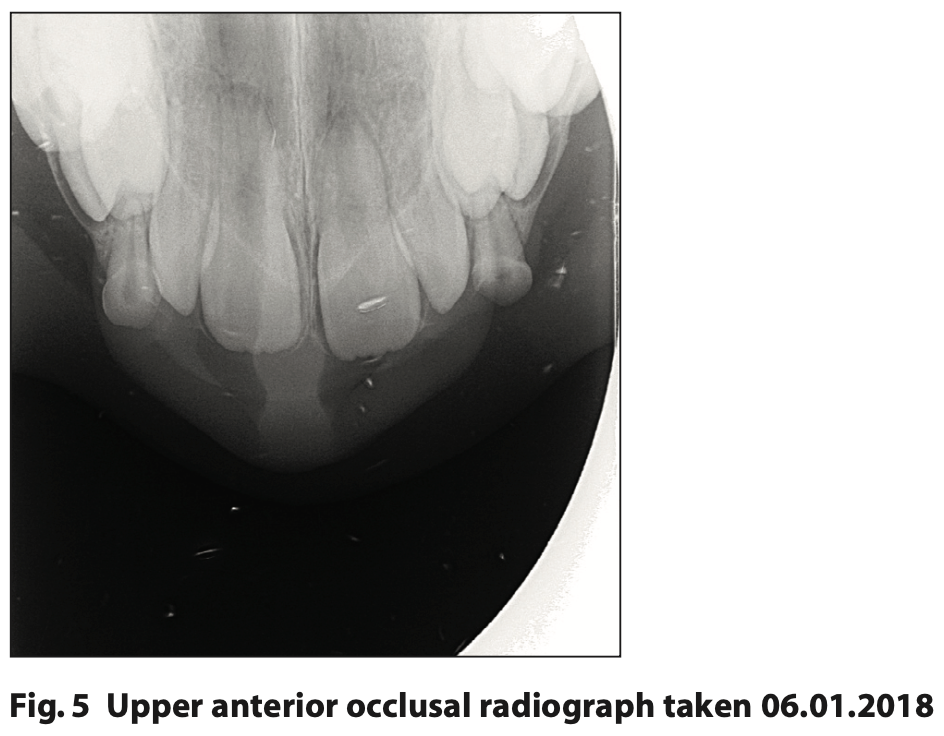

A Dental Panoramic Tomograph (DPT) was taken to assess the dental development, presence of LR5 and treatment planning of the first permanent adult molars as shown in Figure 4. Radiolucent lesions were noted in UR6, UL6 and LL6 indicating caries and a radiolucency affecting LRE (lower right second deciduous molar) indicating distal root resorption. Hypodontia of LR5 was confirmed and there was no sign of the lower third molars developing. The bifurcations of the second permanent molars were forming in the lower arch and just starting to form in the upper arch. In addition, an upper anterior occlusal was taken to assess the presence of upper incisors and their stage of root development as can be seen in Figure 5. All four upper incisors (UR1, UR2, UL1 and UL2) were present and root development was as expected for a ten-year-old.

Diagnostic summary

Following a full clinical and radiographic examination, the following diagnoses were made:

- High caries risk

- Dental Anxiety, Frankl 2

- Generalised Gingivitis

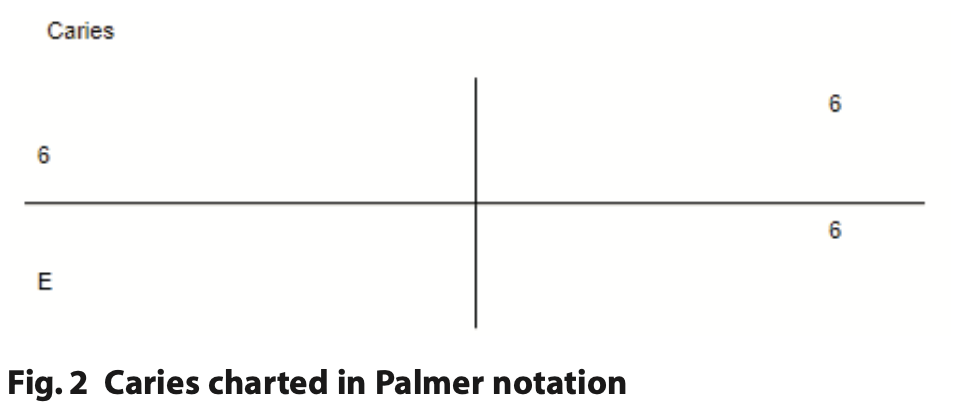

- Caries UR6, UL6, LL6, LRE

- Distal root resorption LRE

- Hypodontia LR5

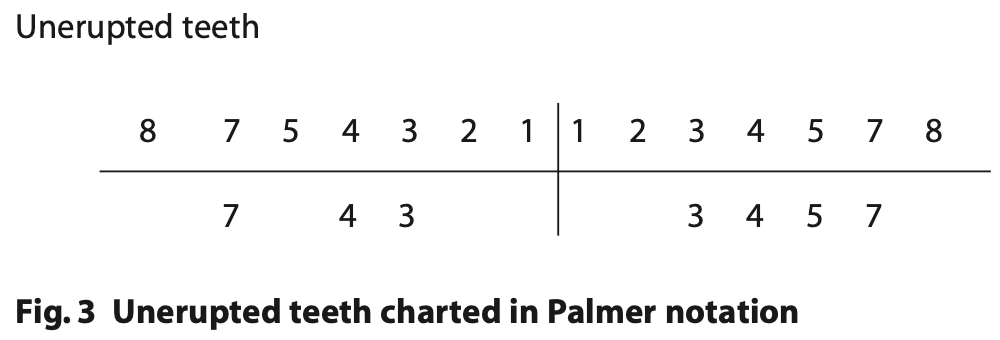

- Delayed eruption of UR2, UR1, UL1, UL2 (Canines, Premolars and Second permanent molars not erupted by age 14).

Aims and objectives of treatment

The treatment plan was devised in a joint orthodontic paediatric dentistry multidisciplinary clinic.

After discussing the findings with the patient and their parent and obtaining informed consent, we aimed to achieve:

- Acclimatisation to the dental setting with a phased approach, allowing for acceptance of dental treatment

- Prevention of any further dental disease to thereby reduce their risk of caries and periodontal disease

- The use of timed extractions to allow spontaneous space closure during dental development

- Monitor dental development.

Treatment undertaken

Our plan began with preventive measures to ensure interventions would have longevity and the patient continued to maintain their oral health. Oral hygiene advice and dietary analysis and advice were tailored to the patient. As per Delivering Better Oral Health prescribed fluoride intervals were reduced to three-monthly.

It was essential to ensure we maximised the efficacy of our non- pharmacological behaviour management techniques by using different methods in our armamentarium including:

- Acclimatisation

- Tell, show, do

- Behaviour shaping

- Positive reinforcement

- Enhanced control.

This ordering, rationale and techniques used will be covered in further detail in the discussion.

As the patient became acclimatised to the dental setting, we introduced treatment and used inhalation sedation as an adjunct to all procedures. Initial management began with soft tissue exposure of unerupted UR1 and UL1 in September 2021. This was followed by the extraction of UL6 and LL6 in November 2021 (the carious LRE had exfoliated in the intervening time and had been lost by August 2021) and subsequent extraction of UR6 and fissure sealant of LR6 in January 2022.

The remaining soft tissue exposures were performed on UL3, UL4, UL5, LL4 and LL5 in March 2023.

During these treatment appointments, nitrous oxide was titrated at 30% with oxygen at 70%, a flow rate of six litres per minute. The patient coped well throughout the treatment appointments.

It should be noted that we planned to review the upper incisors and monitor dental development, however, management of this case was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic as, whilst the department remained open throughout, there was an increased demand for sedation appointments within the hospital setting.1

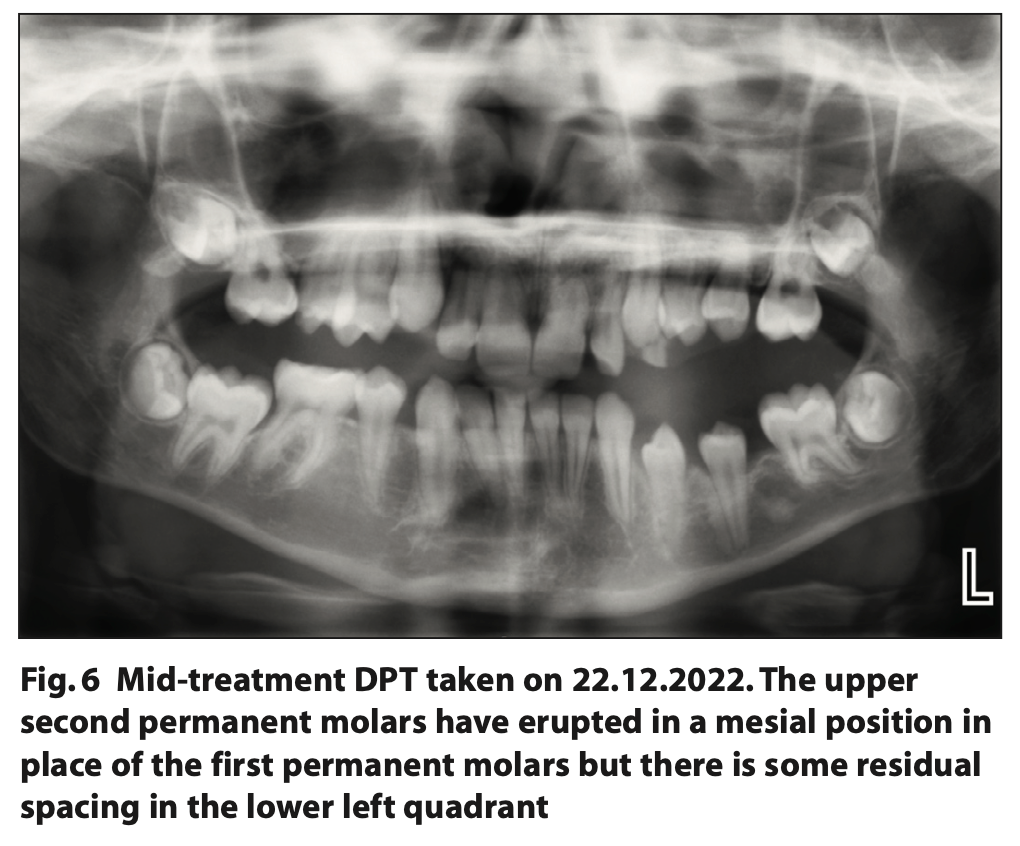

We continued to monitor dental eruption and retook a DPT as shown in Figure 6. This occurred in December 2022 when the patient was 15 years old and demonstrated:

- Continued dental development with good contact between the LR6 and LR4

- No further caries presence

- Non-eruption of the UL345 and LL45 but these were more superficial than in the previous radiograph.

Post-treatment photographs and radiographs

Post-operative photographs were taken on 08.08.2023, demonstrating the eruption of UR12345, UL12345, LL345 and LR34 within the line of the dental arch as can be seen in Figure 7.

Long term treatment and future considerations

Our plan is to continue to monitor the dental development, reinforce oral hygiene, with regular review and consider fixed orthodontic appliance therapy to close residual spacing once oral hygiene has significantly improved.

Discussion and reflection

Eruption disturbances can be broadly classified as disturbances related to time and disturbances related to position. Time-related disturbances include premature eruption, delayed eruption or impactions.2,3

Although root development represents the fundamental biologic parameter for tooth eruption, chronological age at presentation is used as the first criterion in the establishment of the diagnosis of prematurity or a delay in eruption.4

Delayed eruption may occur due to supernumerary teeth, trauma, dilacerations, congenitally displaced, ectopic development cysts, tumours, over-retained primary teeth, dense mucoperiosteum, lack of space, ankylosis and abnormal morphology.5

In this case, delayed eruption of the permanent teeth was attributed to mucosal barriers in the path of eruption. Formation of a dense mucoperiosteum that acts as a physical barrier to eruption can occur during development but in this case, may have been exacerbated by the early extraction of the upper primary incisors and some of the primary molars under five years of age.6

Hypodontia is defined as the developmental absence of one or more teeth, which can affect both the primary and the permanent dentition. The prevalence of this in permanent dentition is estimated at 3.5 to 6% in the British population.7 Over 80% of patients with hypodontia present with the absence of one or two missing teeth.8

In patients with hypodontia of the second mandibular premolar, extraction of the second primary molar before 11 years of age and before the eruption of the second permanent molar may result in spontaneous space closure.9 In this case we can see a good contact point between the LR6 and the LR4.

The patient made tremendous progress in the early acclimatisation appointments, and discussions involved the patient's potential to cope with surgical treatment and extractions under inhalation sedation. Within the paediatric dental department, tailored inhalation sedation leaflets are used to explain required and frequently asked questions, aiding the consent process. A nasal mask is then given to the child to take home and practice wearing.10

Inhalation sedation was commenced at the second visit and was used for four visits. Behavioural management techniques were used in conjunction with inhalation sedation, including tell, show, do; guided imagery; positive reinforcement and stop signals.

Moreover, the patient responded very well to guided imagery during the inhalation sedation. Throughout, the patient was given autonomy and control using stop signals if at any point he became uncomfortable during the procedures.

Overall, the combinational use of pharmacological anxiolytic techniques such as inhalation sedation in combination with behavioural management techniques has led to a successful outcome and demonstrates its importance as an adjunct in a phased treatment approach, avoiding the requirement of general anaesthetic.

References

1. Patel K B, Fong F, Kaur R and Whatling R. Children's dentistry in secondary care during COVID-19. Dent Update. 2000;47:652-661. doi.10.12968/DENU.2020.47.8.652.

2. Kuvvetli S S, Seymen F andGencay K. Management of an unerupted dilacerated maxillary central incisor: A case report. Dental Traumatology. 2007;23:257–61. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00424.x

3. Kramer R M and Williams A C. The incidence of impacted teeth. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path. 1970;29:237–41. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(70)90091-5.

4. Pallavi C, Dhanasekar P, Joybell C and Moses J. Impacted supernumerary teeth along with the presence of impacted maxillary central incisors. International J Orth Rehab. 2020;11:43. doi:10.4103/ijor.ijor_47_19.

5. Grover P S and Lorton L. The incidence of unerupted permanent teeth and related clinical cases. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path. 1985;59:420–5. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(85)90070-2.

6. Huber K, Suri L and Taneja P. Eruption disturbances of the maxillary incisors:a literature review. J Clini Ped Dent. 2008;32:221–30. doi:10.17796/jcpd.32.3.m175g328l100x745.

7. Muller T P, Hill I N, Petersen A C and Blayney J R. A survey of congenitally missing permanent teeth. JADA. 1970;81:101–7. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1970.0151.

8. Brook A H. Variables and criteria in prevalence studies of dental anomalies of number, form and size. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1975;3:288–93. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1975.tb00326.x

9. Joondeph D R and McNeill R W. Congenitally absent second premolars: An interceptive approach. Am J Orth. 1971;59:50–66. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(71)90215-6.

10. Effectiveness Programme SD. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme prevention and management of dental caries in children. dental clinical guidance. part III. Management of caries in permanent molars. management of caries in primary teeth. SDCEP. 2012;65:440–64. doi:10.5604/00114553.1001272.