Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Dental treatment for a 15-year-old patient with Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome, under intravenous sedation with midazolam: a case report

J. Coomar BDS, PG-Cert (Sed. and Dent. Ed.) Community Dental Officer, Bedfordshire Community Dental Services CIC, Houghton Regis Health Centre, Bedford Square, Tithe Farm Road, Houghton Regis, Bedfordshire, LU5 5ES

Correspondence to: Jacqueline Coomar

Email: Jacqueline.coomar@cds-cic.co.uk

Coomar J. Dental treatment for a 15-year-old patient with Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome, under intravenous sedation with midazolam: a case report. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(1): 47-49

Case Summary

A 15-year-old male with Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome (NCBRS), presented for a routine examination complaining of lower left tooth pain. NCBRS is a very rare genetic condition caused by mutations in the SMRCA2 gene, affecting chromatin remodelling where patients can exhibit delayed eruption of permanent teeth, spaced dentition and hypodontia.1 He also has a severe learning disability, heart murmur, ADHD, psoriasis, asthma (mild), scoliosis and limited speech.

He exhibited severe crowding, an anterior open bite, multiple retained deciduous teeth, a fractured upper left central incisor and a grossly carious upper right deciduous second molar. An orthodontic opinion was sought and the extraction of all deciduous teeth was advised. After discussing treatment options with his parent, intravenous sedation was chosen due to the patient’s challenging co-operation for extractions. The treatment was completed over three appointments under intravenous sedation, with an operative score of three and a general anaesthetic was avoided.

Patient details

Gender: Male

Age at start of treatment: 15 years old

Pre-treatment assessment

History of presenting patient's complaints

Some pain from his LLCD (which he pointed to).

Relevant medical history

Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome (NCBRS), severe learning disability, heart murmur, ADHD, psoriasis, mild asthma, scoliosis

Medications

Salbutamol PRN, Melatonin and Risperidone

Dental history

Regular attender

Treatment appointments

Tuesday, 28th February 2018: XLA retained ULA using the Wand STA. Great co-operation.

Friday, 27th April 2018: Emergency appointment. Patient fell at school, fracturing his UL1 into dentine (mesial-incisal) and UR1 into enamel (incisal). There was no tenderness to percussion or mobility. Not co-operative for a peri-apical radiograph.

Wednesday, 13th June 2018: Composite restorations UR1 and UL1.

Friday, 29th June 2018: Emergency appointment. Lost filling of UL1 which was restored with composite.

Monday, 29th October 2018: Emergency appointment. Lost restoration UL1, which was restored with composite.

Tuesday, 12th April 2021: Successful XLA of retained ULC and LRC using Wand STA.

Friday, 3rd December 2021: Attempted XLA LLCD with Wand STA. He was co-operative for LA but not for extractions.

Clinical examination

Extraoral examination

- Nothing abnormal detected

Intraoral examination

- Soft tissues: Nothing abnormal detected

- Gingivae: Some inflammation due to plaque

- Caries: URE (into pulp)

- Restorations: UR1 incisal edge composite (sound) and missing composite UL1 (mesial-incisal)

Infection

Nil

Mobile teeth

Nil

Teeth present

UR12CE6 UL1234E6 LL123C4DE6 LR1234E6

BPE

unable to measure due to co-operation level

Occlusion

Orthodontic assessment: Class 2 division 1 incisor relationship, spaced arches and anterior open bite, UL3 partially erupted and UR3 palpable, buccally displaced LL34 due to retained LLCD

Tooth wear

low

General radiographic examination

Radiographs taken and why

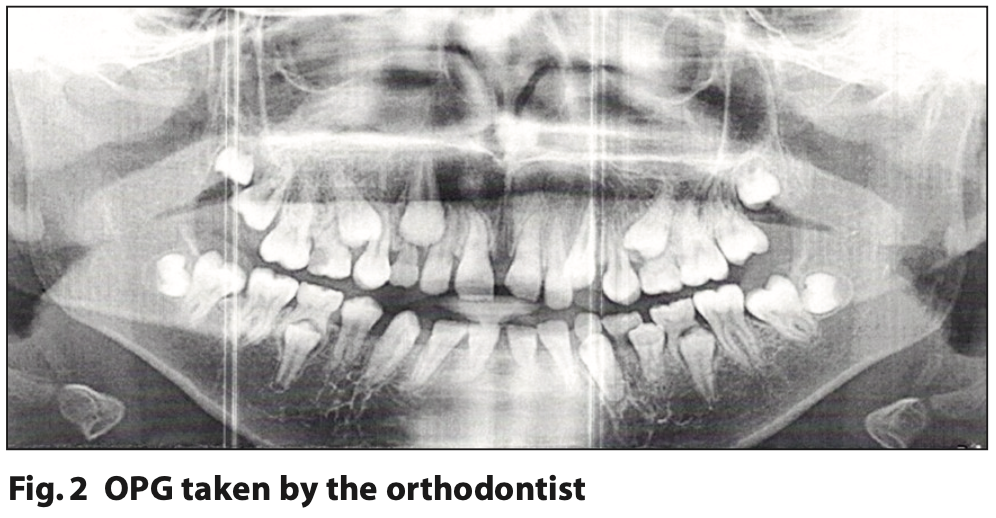

OPG taken by the orthodontist Tuesday, 17th January 2022 to assess teeth present.

Radiographic findings

• UREdo carious lesion into pulp

• Teeth present UR12CE6 UL1234E6 LL123C4DE6 LR1234E6

• Unerupted UR34578 UL578 LL34578 LR578

• Horizontal bone levels fine

• Grade: A

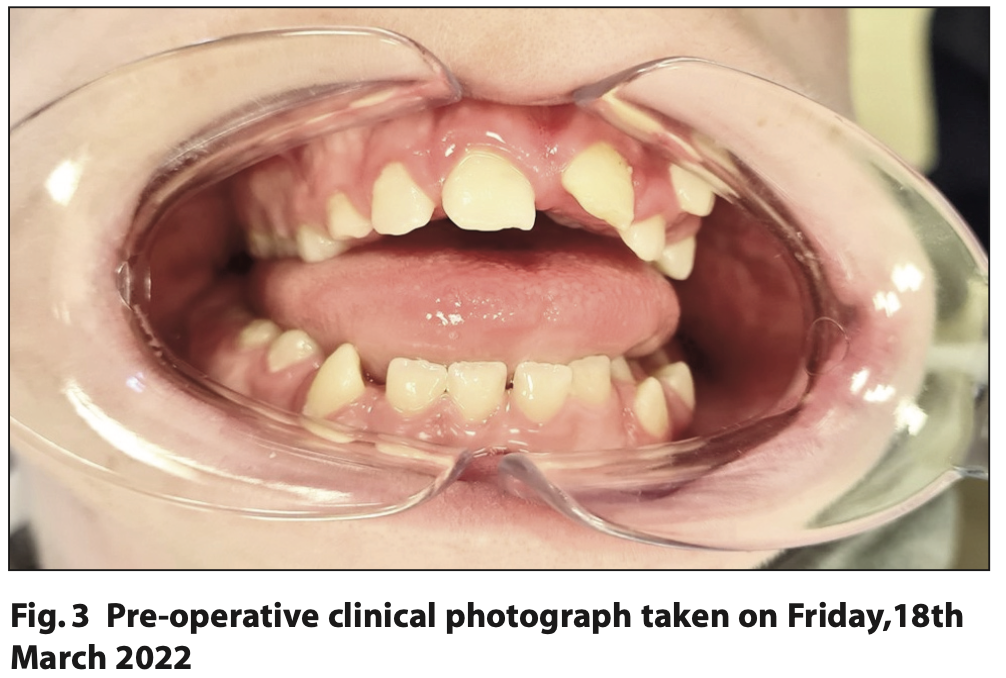

Pre-treatment photographs

intraoral

Diagnostic summary

- Defective restoration vital UL1 incisally (multiple replacements)

- Grossly carious UREdo into pulp

- Retained URCE, ULE, LLCDE, LRE (delayed eruption of permanent teeth)

Aims and objectives of treatment

- To aid the eruption and prevent displacement of permanent teeth

- To restore and prevent the loss of vitality of UL1 post trauma

Treatment plan

- Orthodontic referral sent to Luton and Dunstable hospital – Orthodontist request to XLA URCE ULE LLCDE LRE

- Restore UL1 with composite

- Fissure seal UR6 UL6 LL6 LR6

Treatment undertaken

- Friday, 18th March 2022: XLA LLCDE under IV sedation. Cannulation was a real challenge, but we managed with the parents holding patient’s hand. Operative score of three. 10 mg midazolam was administered.

- Monday, 9th May 2022: XLA UREC LRE under IV sedation. Operative score of three, but much better than the first appointment. 10 mg midazolam was administered.

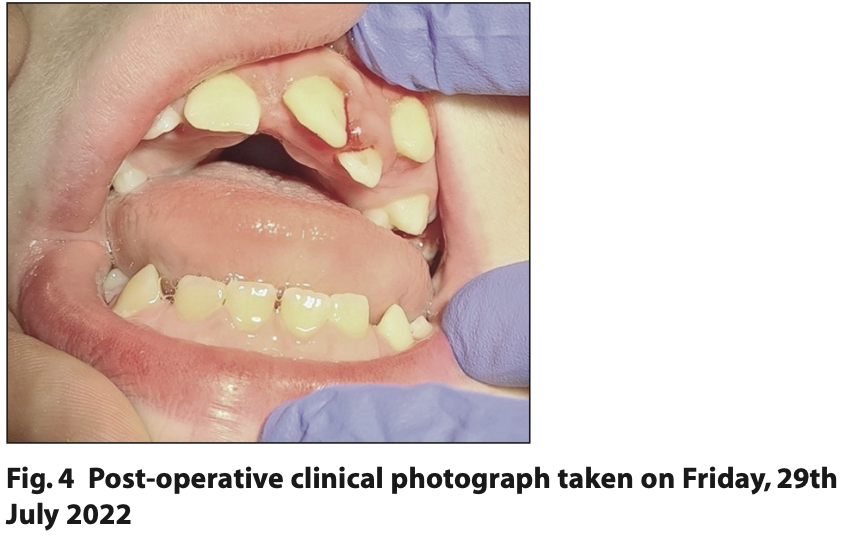

- Friday, 29th July 2022: Restoration of UL1 and XLA ULE under IV sedation. Operative score of three. Abandoned fissure sealants due to patient’s co-operation level and inability to obtain sufficient moisture control. 8 mg midazolam was administered.

Long term treatment and future considerations

Routine examinations, monitoring of UL1 and acclimatisation to dental treatment without sedation. Unfortunately, the patient is not co-operative enough for fixed orthodontic appliances at present, but he is under review with the orthodontist.

Discussion and reflection

This marks my first encounter with a patient diagnosed with NCBRS, a very rare congenital genetic disorder. There are only 100 cases reported and it has been found to be caused by mutations in the SMRCA2 gene, affecting chromatin remodelling.1 In relation to their dentition, affected individuals often exhibit delayed eruption of permanent teeth, spaced dentition, hypodontia and encounter challenges in speech and oral hygiene practices.2,3 This patient presented with multiple retained deciduous teeth, an anterior open bite, spaced dentition and suboptimal oral hygiene.

Other features that patients with NCBRS may present with are ‘…sparse scalp hair, small head size (microcephaly), distinct facial features, short stature, prominent finger joints, unusually short fingers and toes (brachydactyly), recurrent seizures (epilepsy), and moderate to severe intellectual disability with impaired language development.’ 2 This patient exhibited some of these physical features and has a severe learning disability, but he can communicate verbally and has some understanding.

This patient has a heart murmur and, traditionally, prophylactic antibiotics may have been prescribed prior to dental treatment for such patients. According to the NICE clinical guidance (2018), patients with a heart murmur are not considered to be a patient of special consideration for increased risk of infective endocarditis. Therefore a medical practitioner’s opinion or antibiotics were not required for this patient.

The patient previously co-operated with the extractions of his ULA (2018) URC and ULC (2021), but he then became uncooperative for the extractions of his LLCD. This could have been due to a few reasons, such as that his ULA was mobile and his URC and ULC were slightly mobile, therefore required less pressure and movement during the extractions. His father also mentioned that he may have been traumatised by recent immunisations.

During discussions regarding treatment options with his father, the potential limitations of utilising IV sedation due to the patient’s uncooperative behaviour were explicitly conveyed, as well as the possibility of paradoxical effects from midazolam on patients under 16 years of age. Despite these concerns, his father expressed a desire to proceed with IV sedation aiming to circumvent the need for general anaesthesia. This was especially important as there is little information available for patients with NCBRS undergoing general anaesthesia.1

I am pleased that the treatment was successfully completed under IV sedation, where considerable credit belongs to the patient's parents’ proactive involvement and determination. Their active participation, including the light holding of their son and emotional support, proved invaluable and enabled treatment to be carried out safely. The operative score given for all appointments was a three because the patient moved around intermittently during treatment. Consequently, obtaining good clinical photographs was a challenge. Notably, his anxiety decreased at each subsequent appointment as cannulation became easier each time. His parents were pleased that general anaesthesia was avoided and they were happy with the treatment outcomes.

The patient follows a low sugar diet. I reinforced the need for good oral hygiene to his parents. I do not anticipate that he will need treatment for caries, but he may require a replacement of his UL1 restoration as moisture control was difficult to obtain. With further acclimatisation and behavioural management techniques, I will endeavour to complete any necessary treatment in the future. Should IV sedation be the only modality to aid this, then I am hopeful that it will be helpful.

For similar patients in the future, I will consider using a premedication such as intranasal midazolam, which would have likely facilitated in this patient’s acceptance of cannula placement. Currently, I am undergoing supervised training to acquire the necessary skills to independently administer midazolam in this way. Nevertheless, with the assistance of EMLA cream, I managed to cannulate him during all three appointments, albeit with some difficulty. Multiple drug IV sedation may also be considered for him in the future if needed, which could result in improved co- operation for treatment. In addition to this, formal training in clinical holding for myself may prove helpful for similar patients where it is in their best interests and clinically justified.

Treating patients with learning disabilities using IV sedation can present challenges, as their individual reactions and responses to sedation may vary, making it difficult to predict and anticipate their specific needs during the procedure. It is important to manage patients', and their parents', expectations of IV sedation and to inform them of the limitations, particularly in patients whose outcomes may be uncertain. As of the current knowledge, no other case reports in the field of dentistry or sedation specifically focus on patients with NCBRS. Therefore, this case report may hold significant value as it contributes essential information to the existing body of research.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank members of staff from the Community Dental Services CIC. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Goehring M, Choorapoikayil S, Zacharowski K and Messroghli L. Anaesthesia and orphan disease: management of a case of Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome undergoing cleft palate surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 2021; 21:162.

2. MedlinePlus Genetics. Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2022. Online information available at https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/nicolaides-baraitser-syndrome/ (accessed Jun 28 2023).

3. National Library of Medicine. Abdul-Rahman O. Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome. 2015. Online information available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321516/ (accessed Jun 28 2023).