Please click on the tables and figures to enlarge

Cannulation conundrums: what help is available?

A. Gupta*1, BDS, PG Cert, MFDS RCSPG

T. Nagpal2, BDS, PG Cert, PG Dip, MFDS RCSEd

1Oral Surgery Registrar, Southend Hospital, Prittlewell Chase, Southend-On-Sea, SS0 0RY

2Oral Surgery Registrar, Luton and Dunstable Hospital, Luton, LU4 0DZ

*Correspondence to: Ashana Gupta

Email: Ashana.Gupta2@nhs.net

Gupta A, Nagpal T. Cannulation conundrums: what help is available?. SAAD Dig. 2024: 40(II): 117-123

Abstract

A fundamental requirement of intravenous sedation is access. Successful cannulation is vital for delivery of the sedative, reversal agents and for management of medical emergencies. Experienced clinicians, however, will be able to recall occasions where they have struggled to gain intravenous access.

Pre-operatively, the consultation visit can be utilised to prepare the patient for sedation cannulation. Patients can be advised on hydration to improve vein visibility at the time of cannulation. The clinician can also visualise blood vessels that would be suitable for cannulation at the initial assessment. Application of the Adult Difficult Intravenous Access Scale to grade cannulation difficulty is useful for record keeping as well as preparing the clinician for cannulation difficulties and organising appropriate adjuncts. At the time of cannulation, tapping of the vein, placement of warm compresses, milking of veins proximally to distally and application of a tourniquet can increase venous prominence. Adjuncts that can be used include the sphygmomanometer cuff at or below diastolic pressure, transillumination and topical venodilation with nitroglycerine ointment. The availability of portable handheld ultrasound devices has also enabled ultrasound guided cannulation within a dental setting.

This paper provides an algorithm to guide the clinician when managing difficult cannulation.

Introduction

Intravenous (IV) cannula placement is required to administer sedative medication as well as reversal agents. This is often the first clinical stage of delivering conscious sedation, with the exception being those that must be given a form of premedication or alternative sedation technique to aid the acceptance of IV cannulation. It can be argued that being prepared with the full adjunctive armamentarium for successful IV access is crucial as the gold standard for delivery of the sedation reversal agents is through intravenous administration.

Cannulation can be considered a challenging skill with a cross-sectional survey conducted in 25 countries stating a potential failure rate between 31% and 67%.1 Repeated attempts at cannulation can pose a burden to both the patient and healthcare system. Risks associated with repeated cannulation include pain, infection, nerve damage, bleeding, haematoma, air embolism and occlusion.2,3

The average duration for ‘time taken to cannulate’ varies between 32 seconds and two minutes in successful cases of venous access. When access is difficult, reports indicate the time taken can increase to be between 66 seconds and five minutes.4

The Welsh peripheral intravenous cannulation best practice guidelines suggest a maximum of two failed cannulation attempts. Clinical judgement should be exercised and reassessment with senior support, or cannulation adjuncts may be needed.5 This paper aims to inform clinicians of their options to aid adult cannulation and ultimately ensure they are able to gain venous access as efficiently as possible, overcoming arguably the most crucial step to be able to deliver successful conscious sedation.

Pre-operative patient assessment

Venous access should be assessed during the patient’s consultation visit when treatment planning sedation. Consideration of the patient’s medical history is essential as this may complicate cannulation. Relative contraindications for insertion of a peripheral cannula at a particular site may include phlebitis, sclerosed veins, burns, history of trauma, obesity, ipsilateral mastectomy and lymph node dissection.2 Awareness of these factors will enable the sedationist to prepare and choose an appropriate venous access site. Swift cannulation and administration of sedation drugs is an important step in managing the anxious patient.

As part of the consent process, patients should be made aware of the need for cannula insertion, potential insertion sites, the associated risks and potential complications.6,7

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that clinicians make a clinical decision regarding the ideal site and choice of vein before cannulating, to reduce the risk of cannula failure and complications.8 Sites to be avoided include any veins in proximity to arteries, superficial or sclerosed veins. If the patient is postmastectomy in breast cancer treatment, the side associated with breast surgery is best avoided due to the risk of lymphoedema developing post node removal.5

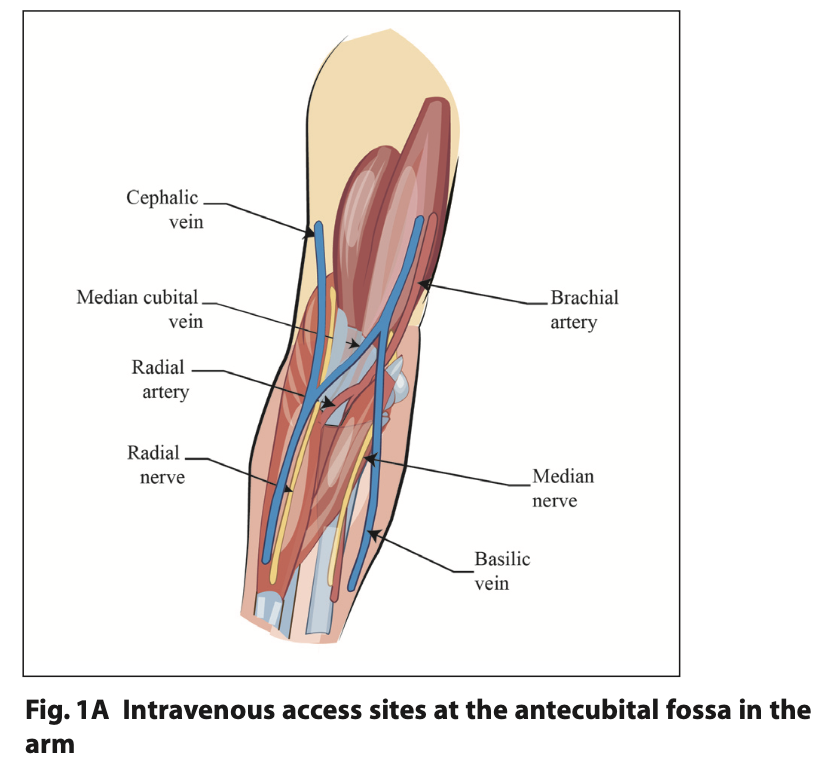

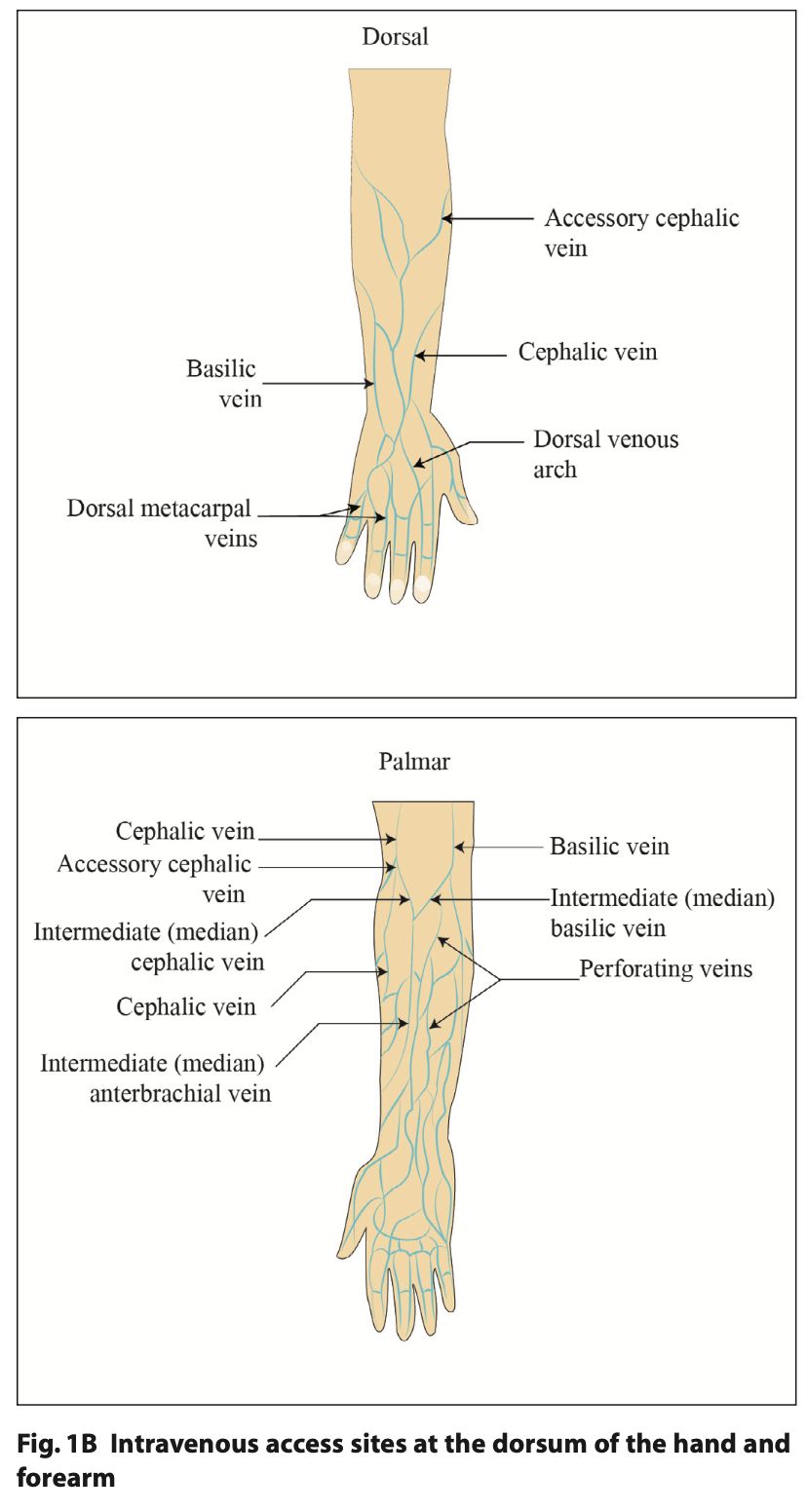

The cephalic or basilic vein on the forearm (Figure 1A), cephalic vein of the wrist and the dorsal metacarpal veins on the back of the hand (Figure 1B) are considered best practice for cannulation.7

Predicting difficult venous access

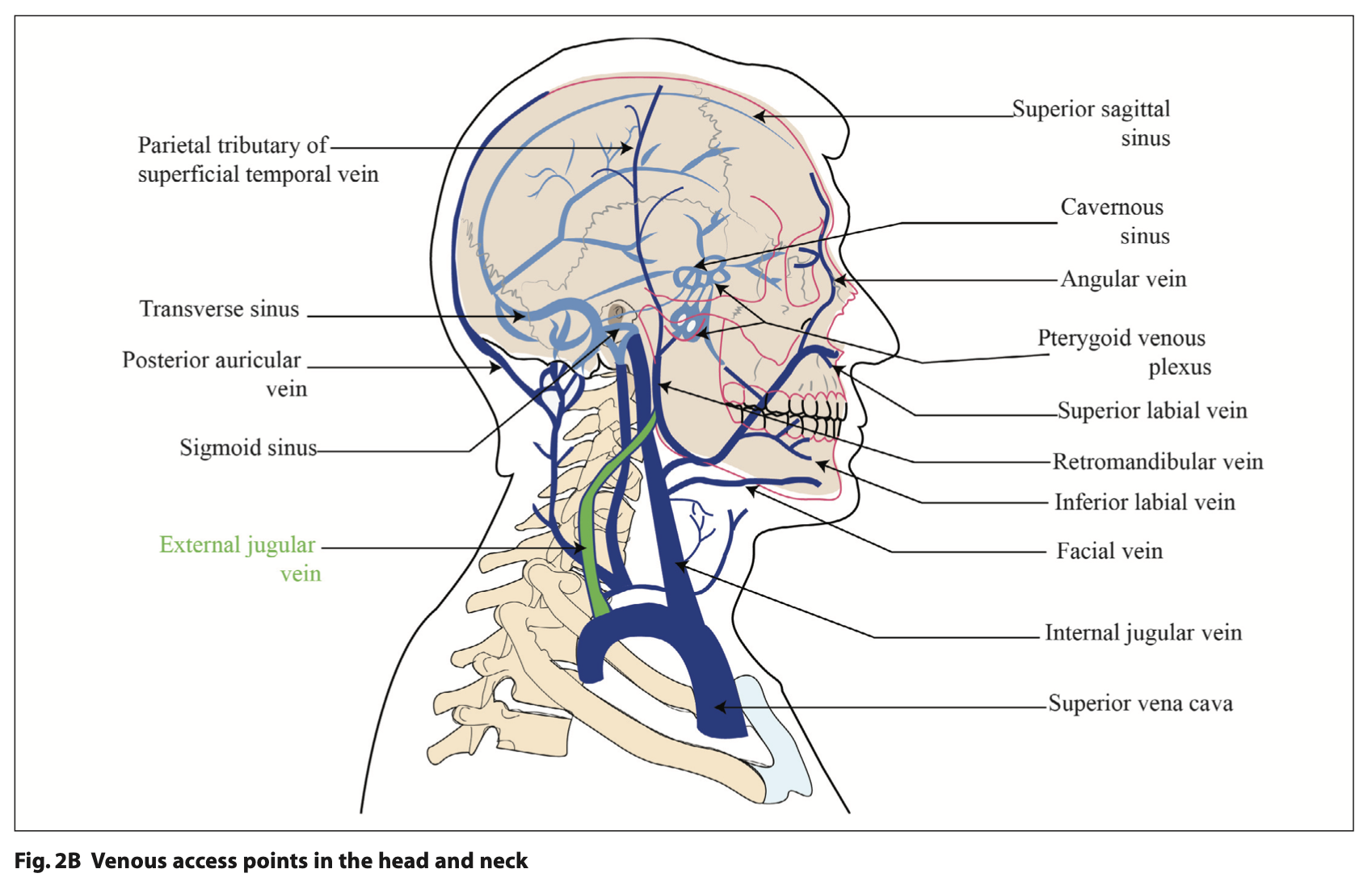

Cannulation can fail for several reasons. These can be categorised to systemic patient factors, local patient factors or clinician factors as shown in Table 1.

Systemic factors

Patients assessed to be American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) I and ASA II are appropriate for management in a primary dental care setting for conscious sedation, those who are considered ASA III should be referred to secondary or tertiary settings and are likely to have more difficult venous access due to a combination of the above factors.

To mitigate some of the preventable factors, appropriate pre-operative instructions should be given to patients attending for sedation to maximise the chances of successful cannulation. Fasting prior to dental conscious sedation is an often-discussed issue. As loss of airway reflexes should never occur in conscious sedation in dentistry, fasting is unnecessary.10,11 Eating and drinking appropriately allows patients to minimise the risk of dehydration prior to attending and increases the visibility of their veins. Secondary or tertiary care settings may have fasting instructions which may contrast with this due to the use of polypharmacy and broad hospital policies also covering our anaesthetic and gastroenterology colleagues and their procedures under conscious sedation.

Local factors

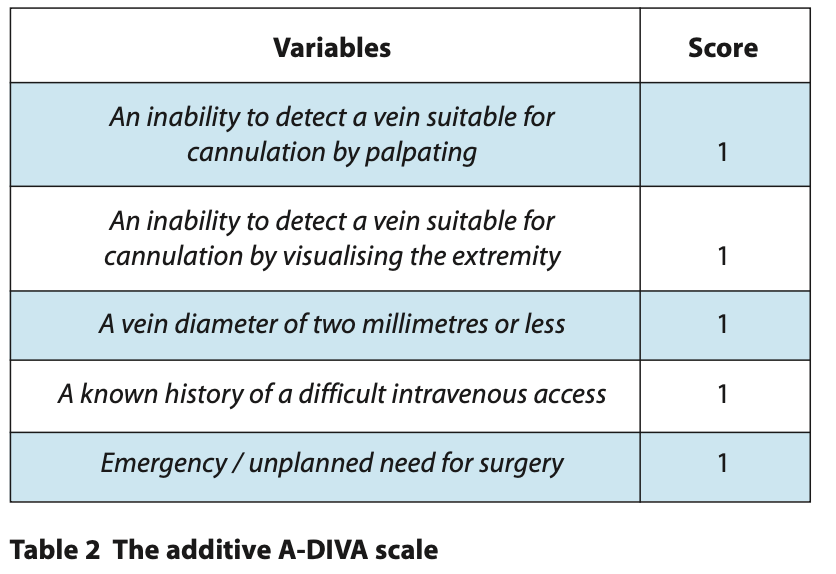

The Adult Difficult Intravenous Access Scale (A-DIVA) is a recently created predictive scale to identify patients with difficult intravenous access. This additive A-DIVA scale predicts the likelihood of a difficult intravenous access in adult patients prospectively, based on clinical observations and five variables (Table 2).12

Each variable is assigned a binary score of zero or one based on ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses. A score of zero to one can be considered low risk for cannulation difficulty. A score of two to three is considered medium risk and a score of four and above can be considered high risk for cannulation difficulty. Applying the A-DIVA scale to surgical patients is a quick aid for the clinician; increasing confidence in successfully inserting a peripheral intravenous catheter on the first attempt and / or preparing the clinician to anticipate difficulty and to organise adjunctive techniques, such as ultrasound, pre-emptively.13

The Difficult Intravenous Access Scale (DIVA) can also be applied to predicting cannulation difficulty in children. It consists of a four-point scale and accounts for age, a history of premature birth, skin shade, vein visibility and vein palpability.12

A limitation is that the scale was developed by anaesthetists for use in general anaesthetic and Accident and Emergency departments.12 The principles of decision making, however, can be applied to intravenous sedation in the elective dental scenario but with caution due to the difference in intended application.

Clinician factors

Operator experience is a significant factor in successful cannulation.14 In some instances, improved technique can overcome difficulties in cannulation. This article discusses cannulation failures and adjuncts for the experienced clinician which can be utilised when difficult intravenous access is predicted.

Signs of failed cannulation are:15

- Tissuing / extravasation. This occurs if the cannula is inserted beyond the vein. Tissuing can be avoided if the cannula is introduced to the vein at an angle of 15° by the operator

- Haematoma formation. This should be managed by applying a firm pressure dressing and locating an alternative distant site for cannulation

- Intra-arterial cannula insertion. This is at higher risk of occurring when cannulating the dorsum of the hand.

Cannulation complications include:

- Thrombophlebitis: an inflamed vein which can occur due to mechanical trauma from cannulation techniques or cannulating over an area of flexion. It is recognised as hardening of the tissue at the cannulation site, pain and erythema15

- Nerve damage: the median nerves and radial nerves are at most risk during cannulation of the basilic or cephalic vein at the antecubital fossa16

- Unintended arterial cannulation can occur and clinicians should be aware of recognising these signs. Pulsatile bright red blood backflow into the cannula, pain on insertion or blanching at a site distal to cannulation can all be indications. Failure to recognise arterial cannulation and delivery of sedative drugs can lead to severe tissue damage and result in compartment syndrome.15

Adjunctive techniques to aid cannulation

Tourniquet use

The first use of a tourniquet was recorded by Sushruta in 600BC, with use of leather to stop arterial bleeding.17 Within the context of cannulation, the effect of a tourniquet can be achieved by a commercially available wraparound tourniquet devices or by manual compression from an assistant 10 cm to 15 cm from the desired cannulation site. The aim is temporarily to block the venous outflow from the site whilst still allowing enough arterial inflow into the area. This causes a build-up of blood in the veins distal to the tourniquet. The vein therefore becomes temporarily dilated, palpable and easier to access. Another advantage of the tourniquet is that the access vein becomes anchored and is less mobile. It is important to be swift in cannulating as the tourniquet should be removed soon after. Prolonged application can lead to fragility of the vein.18 Once a tourniquet is applied, the patient can then be asked to place the limb downwards towards the ground below the level of the heart so gravity allows venous pooling thus increasing vein prominence.

Sphygmomanometer cuff

An alternative to the torniquet technique is the use of a manual blood pressure machine cuff. The cuff can be placed above the venous access site and inflation pressure set to the patient’s diastolic pressure or just below it, once again, to ensure the appropriate restriction of venous outflow whilst maintaining arterial inflow. This technique may be more successful due to a more accurate control of outflow occlusion; also known as venous stasis.19

Percussion of the vein

The vein should be palpated by the clinician to determine the relative size of the vessel and the direction in which it runs. If the vein is not obvious, the clinician may gently tap the skin directly overlying the vein. If the tapping is too firm, however, pain may cause reflex vasoconstriction. Alternatively, milking the vein proximally to distally may also increase venous palpability.18 Asking the patient to clench their fist whilst palpating the vein can also help to increase its prominence.

Heat therapy

The application of a warm compress or immersing the venous access site in a warm water bath for two to three minutes will help to increase local blood flow and increase venous distension.18 Within a primary care dental setting, heaters used for composite capsules could be used to heat a compress, taking care to avoid heat related trauma.

Transillumination

Transilluminating devices use near infrared light-emitting diodes (NIR-LED). The image is created due to the presence of deoxyhaemoglobin in venous blood which absorbs the red infrared light and illuminates the veins as dark lines on the skin surface. This gives the clinician a visual aid to determine where to palpate for veins.20

Non-invasive vein illumination devices, eg AccuVein AV400 device, have been advocated for use in venepuncture or cannulation within the National Health Service (NHS) by NICE. The device can be used by any healthcare professional trained in intravenous cannulation including nurses and surgeons. The distributor provides initial training and education in using the device. Research has shown that vein finder devices reduce the rate at which the insertion site needs re-palpating after skin cleansing21 and can significantly increase intravenous access success rates with a 26% success rate at cannulation compared to only 19% success rate with visualisation or palpation of the vein.9

The device has an NHS acquisition cost of £3,300 + VAT and there may be additional costs for hands-free elements. Previous studies argued that poor vein visibility can make IV cannulation a challenge in children with dark skin colour even with the use of near infrared vascular imaging devices.22

Venodilatation drugs

Topical ointments may be utilised to achieve venodilatation and increase blood flow. Nitroglycerin is broken down into nitric oxide. This causes relaxation of the smooth muscle of the blood vessel, causing increased blood flow. Application of 2% to 4% nitroglycerin ointment for at least two to three minutes applied over half an inch spread of skin can provide sufficient venous distension and equates to a dose of 7.5 mg nitroglycerin. Research shows fewer attempts at cannulation were required in subjects that had an application of nitroglycerin ointment when compared to the control group.23 The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also provide some guidance on the use of nitroglycerin transdermal ointment and recommend that heart rate and blood pressure should be monitored throughout.24

Ultrasound guidance

Ultrasound +/- doppler should be considered if the vessel cannot be seen directly or palpated, viewed with a transillumination device or peripheral venous cannulation is considered to be difficult. This is based on the recommendation by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.25 The ultrasound can also be used to view nearby anatomy that must be avoided during cannulation, for example, the radial nerve that is close to the cephalic vein in the forearm (Figure 1A).

Research shows a 10% higher initial and second attempt success rate when ultrasound guidance was used for vein localisation compared to conventional palpation techniques. Ultrasound guided cannulation shows promising results in most studies. Researchers cannulating the basilic and brachial vein under ultrasound guidance reported a 91% success rate. Complications were limited to paraesthesia in one percent of cases.26,27

Two main types of ultrasound techniques can be used for cannulation. This includes audio guided doppler ultrasound which is not widely utilised. The most commonly used technique is the two-dimensional ultrasound scan that provides grey scale images of the anatomy.

The equipment recommended for intravenous cannulation under ultrasound guidance includes:

- An ultrasound machine with 7.5MHz or higher frequency

- A linear array probe also known as transducer

- A sterile lubricating gel.

The cost of the portable ultrasound machines is between £7,000 and £15,000.

For cannulation guidance, the transverse and cross-sectional view give the best view of the orientation of veins and arteries in relation to each other. Longitudinal views can be used to view the needle within the vein to ensure accurate intraluminal placement.28

Ultrasound scanning use and interpretation require the clinician to undergo further training but key features to look for include linear grey or black shadows beneath the skin surface. Compression will cause the shadow to disappear if it is a vein as the lumen closes on compression whereas an artery lumen will remain open. The cannula can be guided into the vein in real time using the ultrasound scanner to visualise and ensure the needle tip remains in the vein.25 Within secondary services, clinicians may be able to familiarise themselves with this technique by working alongside anaesthetists, consultants in Accident and Emergency departments and radiologists where this technology is more commonly used.

Alternative access site

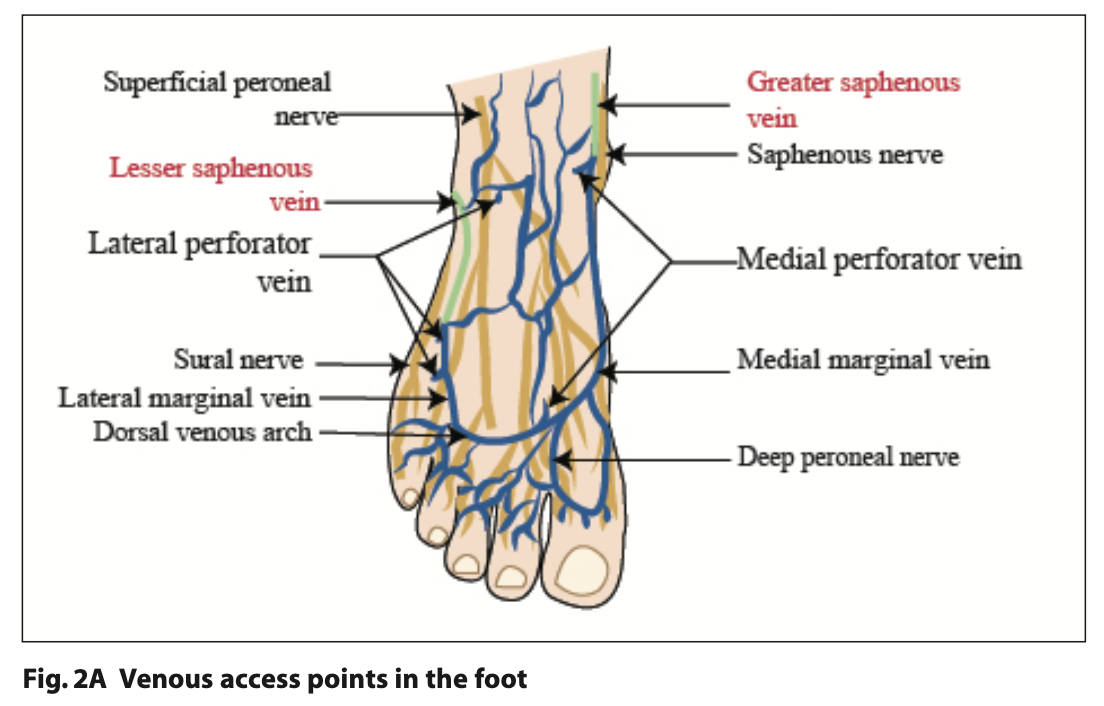

It should be noted that peripheral venous access in intravenous drug misuse can be complicated by fibrosis of the veins from repeated cannulation attempts. In such cases, identifying suitable veins for venous access can be extremely challenging. Alternative venous access sites can be located in the foot, leg and include the deep brachial vein in the arm, however these should only be attempted in a secondary care setting by experienced clinicians. Complete, valid and informed consent must be obtained from the patient to cannulate difficult access sites.

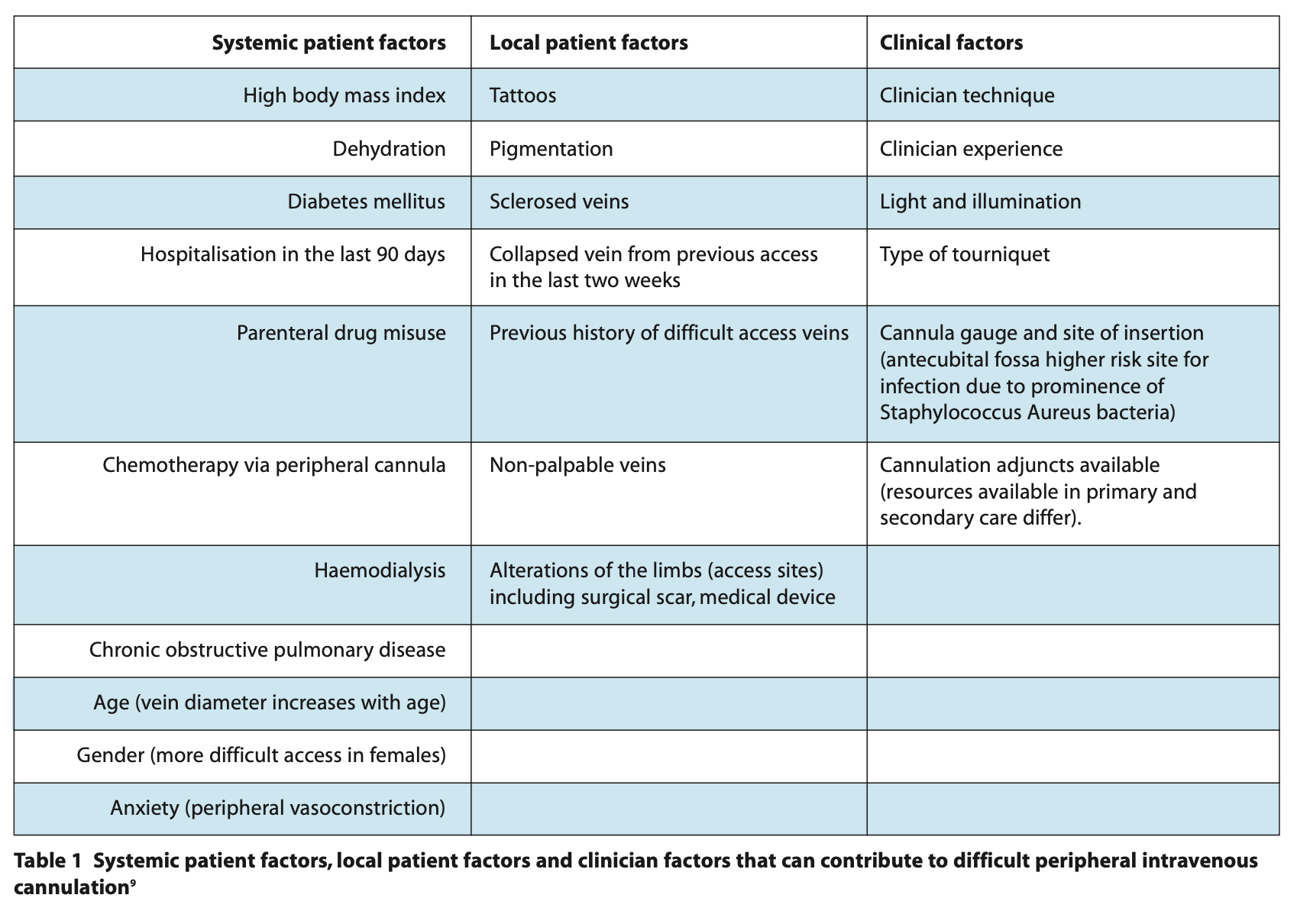

For reference, Figure 2 demonstrates some of the alternative venous access points; such as the lesser saphenous and great saphenous vein in the foot (Figure 2A) and the external jugular vein in the neck (Figure 2B).

Nitrous oxide inhalation

Needle phobia is a barrier for cannulation. There is a greater degree of peripheral vasoconstriction in response to acute mental stress.29 Nitrous oxide inhalation sedation has been shown to reduce anxiety levels30 and is a well-known vasodilator.31 Therefore it is an excellent facilitator of cannulation for needle-phobic patients that do not have a clearly accessible vein.

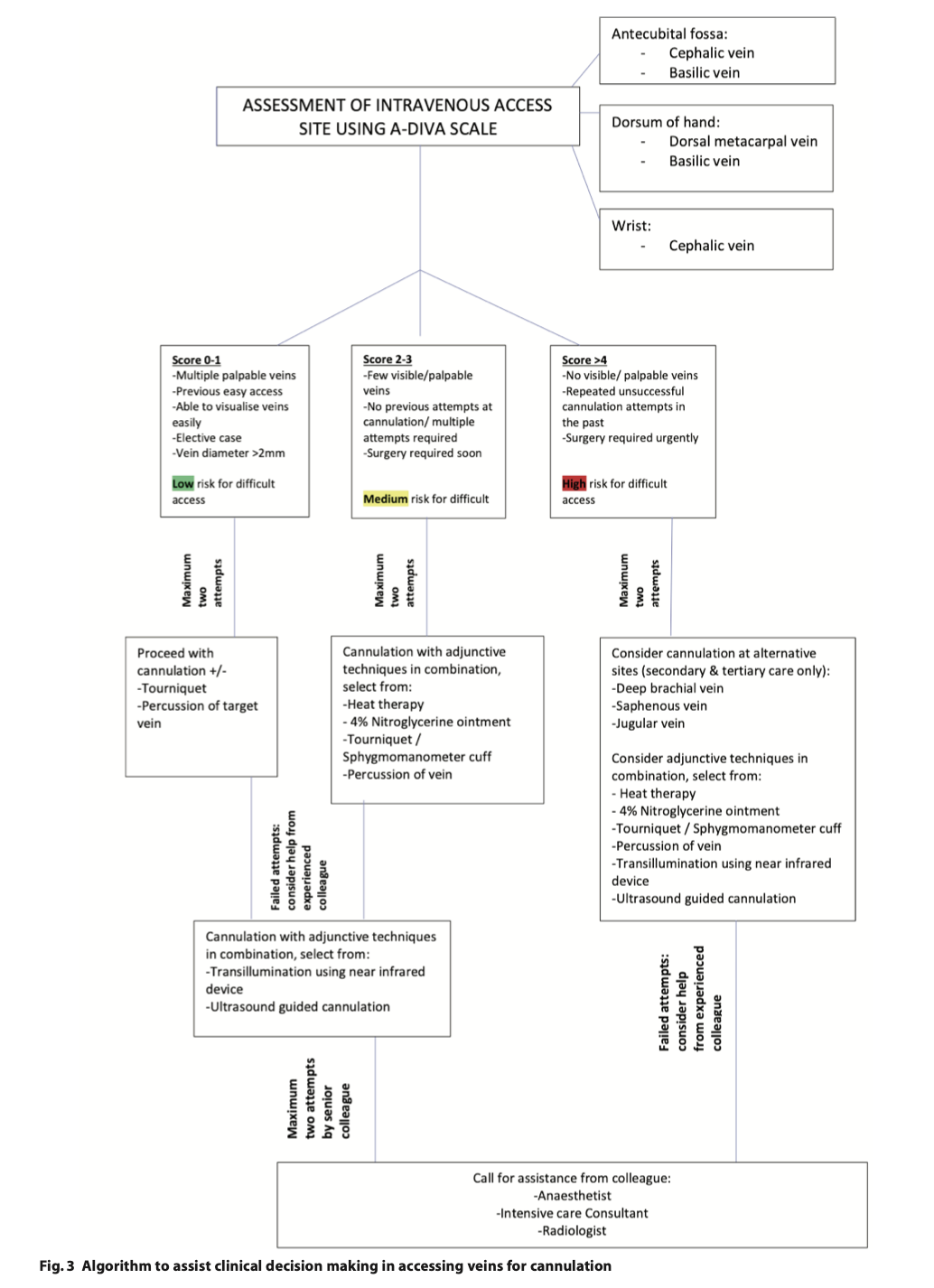

Decision-making algorithm for sedationists

There are a variety of methods which can be utilised to improve peripheral venous access. The resources available may differ depending on the setting in which the sedation is being provided. The following decision-making algorithm (Figure 3) may be applied to aid the clinician’s approach.

Initial recognition of difficult venous access from the outset is crucial to limiting any distress to patients and clinicians and to reducing the incidence of multiple failed attempts at cannulation. By applying the access algorithm (Figure 3), early identification of factors which may make intravenous access more difficult is clearer and informed decision-making to aid venepuncture is therefore possible. Whilst the guidance suggests a maximum of two attempts, clinical judgement is required as to whether further attempts with improved technique is in the patient’s best interests. Using adjunctive measures may lengthen the time taken to cannulate, but is likely to reduce the number of attempts required to cannulate.

Maximising clinical technique to cannulate

In the author’s experience, techniques that can improve cannulation success include pulling the skin overlying the venous access site with the supporting hand in order to stabilise the vein and to avoid snagging the skin with needle entry. If the needle bevel is found to be in contact with the vein wall, this can cause leakage of the sedative into the tissue fluid. This can be corrected by gently pulling the skin, this will separate the bevel from the vein wall.

The clinician must be willing to undertake further training to use adjuncts such as ultrasonography and ensure a steady flow of cases in order to maintain the relevant level of skill. To build confidence, clinicians can use ultrasound assistance for low-risk access points in order to increase familiarity. This practice is acceptable so long as it is not detrimental to the patient’s care and would not compromise any outcome. The current level of resources tailored specifically to those performing conscious sedation in a dental care setting is limited. There is scope for a course to be designed that can would incorporate these techniques. There is most definitely an opportunity for charities to create educational resources in this field.

Conclusion

Clinicians are encouraged to provide sedation assessment for patients at the consultation visit. Consultations for intravenous sedation should include assessment and appraisal of possibly difficult venous access in both primary and secondary care settings. The A-DIVA scale can help to grade and quantify the venous access difficulty and usage of the algorithm (Figure 3) may serve as an aide memoire for selecting the appropriate adjuncts to cannulation.

Declarations

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Cooke M, Ullman A J, Ray-Barruel G, Wallis M, Corley A, Rickard C M. Not ‘just’ an intravenous line: Consumer perspectives on peripheral intravenous cannulation (PIVC). An international cross-sectional survey of 25 countries. PloS One 2018; 13: 1-18.

2. Helm R E, Klausner J D, Klemperer J D, Flint L M, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: Peripheral IV catheter failure. J. Infus. Nurs 2015; 38: 189–203.

3. Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation (PIVC) Insertion, Care and Removal (Adults). Sydney: South Eastern Sydney Local Health District, 2021.

4. Jacobson A F, Winslow E H. Variables influencing intravenous catheter insertion difficulty and failure: an analysis of 339 intravenous catheter insertions. Heart & Lung. J acute and critical care 2005, 34: 345–359.

5. Peripheral intravenous cannulation best practice guidelines issue 2.1. Wales: University health board, 2017.

6. Dougherty L. The Royal Marsden Hospital manual of clinical nursing procedures, 9th ed.. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 2015.

7. Thomas R K. Practical medical procedures at a glance. 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

8. Intravenous fluid therapy in adults in hospital. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013.

9. Pan C T, Francisco M D, Yen C K, Wang S Y, Shiue Y L. Vein Pattern Locating Technology for Cannulation: A Review of the Low-Cost Vein Finder Prototypes Utilizing near Infrared (NIR) Light to Improve Peripheral Subcutaneous Vein Selection for Phlebotomy. Sensors (Basel) 2019; 19: 1-17.

10. Conscious Sedation in the Provision of Dental Care. London: Department of Health, 2003.

11. Thorpe R J, Benger J. Pre-procedural fasting in emergency sedation. Emerg Med J 2010; 27: 254–261.

12. Van Loon F H J, van Hooff L W E, de Boer H D, et al. The Modified A-DIVA Scale as a Predictive Tool for Prospective Identification of Adult Patients at Risk of a Difficult Intravenous Access: A Multicenter Validation Study. J. Clin. Med 2019; 8: 1-14.

13. Van Loon F H J, Puijn L A P M, Houterman S, Bouwman A R A. Development of the A-DIVA Scale: A Clinical Predictive Scale to Identify Difficult Intravenous Access in Adult Patients Based on Clinical Observations. Med 2016; 95: 1-8.

14. Rippey J C, Carr P J, Cooke M, Higgins N, and Rickard C M. Predicting and preventing peripheral intravenous cannula insertion failure in the emergency department: Clinician ‘gestalt’wins again. Emerg Med Austra 2016; 28: 658-665.

15. Helm R E, Klausner J D, Klemperer J D, Flint L M, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: peripheral IV catheter failure. J Infus Nurs. 2015; 38: 189-203.

16. Stevens R j, Mahadevan V, Moss A L. injury to the lateral cutaneous nerve of forearm after venous cannulation: a case report and literature review. Clin Anat. 2012; 25:659-662.

17. Bhattacharya S. Sushrutha - our proud heritage. Indian J Plast Surg 2009; 42: 223-225.

18. Mbamalu D. Banerjee A. Methods of obtaining peripheral venous access in difficult situations. Postgrad Med J 1999; 75: 459–462.

19. Datta S, Hanning C D. How to insert a peripheral venous cannula. Brit J hosp med 1990; 43: 67-69.

20. Chiao F B, Resta-Flarer F, Lesser J, et al. Vein visualization: Patient characteristic factors and efficacy of a new infrared vein finder technology. Br. J. Anaesth 2013; 110: 966–971.

21. AccuVein AV400 for vein visualisation. London: Medtech innovation briefing, 2014.

22. Van Der Woude O C, Cuper N J, Getrouw C, Kalman C J, De Graaff J C. The effectiveness of a near-infrared vascular imaging device to support intravenous cannulation in children with dark skin colour; a cluster randomised clinical trial. Anesth analg 2013; 116: 1266-1271.

23. Roberge R J, Kelly M, Evans T C, et al. Facilitated intravenous access through local application of nitro-glycerine ointment. Ann Emerg Med 1987; 16: 546-549.

24. Draft Guidance on Nitroglycerin. Washington: Food and Drug Administration, 2015.

25. van Loon F H J, Buise M P, Claassen J J F, Dierick-van Daele A T M, Bouwman A R A comparison of ultrasound guidance with palpation and direct visualisation for peripheral vein cannulation in adult patients: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Br. J. Anaesth 2018; 121: 358-366.

26. Keyes L E, Frazee B W, Snoey E R, Simon B C, Christy D. Ultrasound-guided brachial and basilic vein cannulation in emergency department patients with difficult intravenous access. Ann emerg med 1999; 34: 711-714.

27. Etezazian S. Evaluation of Success Rate of Ultrasound-Guided Venous Cannulation in Patients with Difficult Venous Access. Iran J Radiol 2010; 7: 61-65.

28. Guidance on the use of ultrasound locating devices for placing central venous catheters. London: National institute for health and care excellence, 2002.

29. Kim J H et al. Peripheral Vasoconstriction During Mental Stress and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. AHA J 2019, 125.

30. Khinda V, Rao D, & Sodhi S P S. Nitrous Oxide Inhalation Sedation Rapid Analgesia in Dentistry: An Overview of Technique, Objectives, Indications, Advantages, Monitoring, and Safety Profile. Intl J clin paed dent 2023, 16: 131–138.

31. Ichinose F, Roberts J D, Zapol W M. Inhaled Nitric oxide: A Selective Pulmonary Vasodilator: Current Uses and Therapeutic Potential. Circulation. 2004;109: 3106–3111.